The final session on the first full day of BGI24 (yesterday) involved a number of round table discussions described as “Interactive Working Groups”.

The one in which I participated looked at possibilities to reduce the risks of AI inducing a catastrophe – where “catastrophe” means the death (or worse!) of large portions of the human population.

Around twelve of us took part, in what was frequently an intense but good-humoured conversation.

The risks we sought to find ways to reduce included:

- AI taking and executing decisions contrary to human wellbeing

- AI being directed by humans who have malign motivations

- AI causing a catastrophe as a result of an internal defect

Not one of the participants in this conversation thought there was any straightforward way to guarantee the permanent reduction of such risks.

We each raised possible approaches (sometimes as thought experiments rather than serious proposals), but in every case, others in the group pointed out fundamental shortcomings of these approaches.

By the end of the session, when the BGI24 organisers suggested the round table conversations should close and people ought to relocate for a drinks reception one floor below, the mood in our group was pretty despondent.

Nevertheless, we agreed that the search should continue for a clearer understanding of possible solutions.

That search is likely to resume as part of the unconference portion of the summit later this week.

A solution – if one exists – is likely to involve a number of different mechanisms, rather than just a single action. These different mechanisms may incorporate refinements of some of the ideas we discussed at our round table.

With the vision that some readers of this blogpost will be able to propose refinements worth investigating, I list below some of what I remember from our round table conversation.

(The following has been written in some haste. I apologise for typos, misunderstandings, and language that is unnecessarily complicated.)

1. Gaining time via restricting access to compute hardware

Some of the AI catastrophic risks can be delayed if it is made more difficult for development teams around the world to access the hardware resources needed to train next generation AI models. For example, teams might be required to obtain a special licence before being able to purchase large quantities of cutting edge hardware.

However, as time passes, it will become easier for such teams to gain access to the hardware resources required to create powerful new generations of AI. That’s because

- New designs or algorithms will likely allow powerful AI to be created using less hardware than is currently required

- Hardware with the requisite power is likely to become increasingly easy to manufacture (as a consequence of, for example, Moore’s Law).

In other words, this approach may reduce the risks of AI catastrophe over the next few years, but it cannot be a comprehensive solution for the longer term.

(But the time gained ought in principle to provide a larger breathing space to devise and explore other possible solutions.)

2. Avoiding an AI having agency

An AI that lacks agency, but is instead just a passive tool, may have less inclination to take and execute actions contrary to human intent.

That may be an argument to research topics such as AI consciousness and AI volition, in order that any AIs created would be pure passive tools.

(Note that such AIs might plausibly still display remarkable creativity and independence of thought, so they would still provide many of the benefits anticipated for advanced AIs.)

Another idea is to avoid the AI having the kind of persistent memory that might lead to the AI gaining a sense of personal identity worth protecting.

However, it is trivially easy for someone to convert a passive AI into a larger system that demonstrates agency.

That could involve two AIs joined together; or (more simply) a human that uses an AI as a tool to achieve their own goals.

Another issue with this approach is that an AI designed to be passive might manifest agency as an unexpected emergent property. That’s because of two areas in which our understanding is currently far from complete:

- The way in which agency arises in biological brains

- The way in which deep neural networks reach their conclusions.

3. Verify AI recommendations before allowing them to act in the real world

This idea is a variant of the previous one. Rather than an AI issuing its recommendations as direct actions on the external world, the AI is operated entirely within an isolated virtual environment.

In this idea, the operation of the AI is carefully studied – ideally taking advantage of analytical tools that identify key aspects of the AI’s internal models – so that the safety of its recommendations can be ascertained. Only at that point are these recommendations actually put into practice.

However, even if we understand how an AI has obtained its results, it can remain unclear whether these results will turn out to aid human flourishing, or instead have catastrophic consequences. Humans who are performing these checks may reach an incorrect conclusion. For example, they may not spot that the AI has made an error in a particular case.

Moreover, even if some AIs are operated in the above manner, other developers may create AIs which, instead, act directly on the real-world. They might believe they are gaining a speed advantage by doing so. In other words, this risk exists as soon as an AI is created outside of the proposed restrictions.

4. Rather than general AI, just develop narrow AI

Regarding risks of catastrophe from AI that arise from AIs reaching the level of AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) or beyond (“superintelligence”), how about restricting AI development to narrow intelligence?

After all, AIs with narrow intelligence can already provide remarkable benefits to humanity, such as the AlphaFold system of DeepMind which has transformed the study of protein interactions, and the AIs created by Insilico Medicine to speed up drug discovery and deployment.

However, AIs with narrow intelligence have already been involved in numerous instances of failure, leading to deaths of hundreds (or in some estimates, thousands) of people.

As narrow intelligence gains in power, it can be expected that the scale of associated disasters is likely to increase, even if the AI remains short of the status of AGI.

Moreover, it may happen that an AI that is expected to remain at the level of narrow intelligence unexpectedly makes the jump to AGI. After all, which kinds of changes need to be made to a narrow AI to convert it to AGI, is still a controversial question.

Finally, even if many AIs are restricted to the level of narrow intelligence, other developers may design and deploy AGIs. They might believe they are gaining a strong competitive advantage by doing so.

5. AIs should check with humans in all cases of uncertainty

This idea is due to Professor Stuart Russell. It is that AIs should always check with humans in any case where there is uncertainty whether humans would approve of an action.

That is, rather than an AI taking actions in pursuit of a pre-assigned goal, the AI has a fundamental drive to determine which actions will meet with human approval.

However, An AI which needs to check with humans ever time it has reached a conclusion will be unable to operate in real-time. The speed at which it operates will be determined by how closely humans are paying attention. Other developers will likely seek to gain a competitive advantage by reducing the number of times humans are asked to provide feedback.

Moreover, different human observers may provide the AI with different feedback. Psychopathic human observers may steer such an AI toward outcomes that are catastrophic for large portions of the population.

6. Protect critical civilisational infrastructure

Rather than applying checks over the output of an AI, how about applying checks on input to any vulnerable parts of our civilisational infrastructure? These include the control systems for nuclear weapons, manufacturing facilities that could generate biological pathogens, and so on.

This idea – championed by Steve Omohundro and Max Tegmark – seeks to solve the problem of “what if someone creates an AI outside of the allowed design?” In this idea, the design and implementation of the AI does not matter. That’s because access to critical civilisational infrastructure is protected against any unsafe access.

(Significantly, these checks protect that infrastructure against flawed human access as well as against flawed AI access.)

The protection relies on tamperproof hardware running secure trusted algorithms that demand to see a proof of the safety of an action before that action is permitted.

It’s an interesting research proposal!

However, the idea relies on us humans being able to identify in advance all the ways in which an AI (with or without some assistance and prompting by a flawed human) could identify that would cause a catastrophe. An AI that is more intelligent than us is likely to find new such methods.

For example, we could put blocks on all existing factories where dangerous biopathogens could be manufactured. But an AI could design and create a new way to create such a pathogen, involving materials and processes that were previously (wrongly) considered to be inherently safe.

7. Take prompt action when dangerous actions are detected

The way we guard against catastrophic actions initiated by humans can be broken down as follows:

- Make a map of all significant threats and vulnerabilities

- Prioritise these vulnerabilities according to perceived likelihood and impact

- Design monitoring processes regarding these vulnerabilities (sometimes called “canary signals”)

- Take prompt action in any case when imminent danger is detected.

How about applying the same method to potential damage involving AI?

However, AIs may be much more powerful and elusive than even the most dangerous of humans. Taking “prompt action” against such an AI may be outside of our capabilities.

Moreover, an AI may deliberately disguise its motivations, deceiving humans (like how some Large Language Models have already done), until it is too late for humans to take appropriate protective action.

(This is sometimes called the “treacherous turn” scenario.)

Finally, as in the previous idea, the process is vulnerable to failure because we humans failed to anticipate all the ways in which an AI might decide to act that would have catastrophically harmful consequences for humans.

8. Anticipate mutual support

The next idea takes a different kind of approach. Rather than seeking to control an AI that is much smarter and more powerful than us, won’t it simply be sufficient to anticipate that these AIs will find some value or benefit from keeping us around?

This is like humans who enjoy having pet dogs, despite these dogs not being as intelligent as us.

For example, AIs might find us funny or quaint in important ways. Or they may need us to handle tasks that they cannot do by themselves.

However, AIs that are truly more capable than humans in every cognitive aspect will be able, if they wish, to create simulations of human-like creatures that are even funnier and quainter than us, but without our current negative aspects.

As for AIs still needing some support from humans for tasks they cannot currently accomplish by themselves, such need is likely to be at best a temporary phase, as AIs quickly self-improve far beyond our levels.

It would be like ants expecting humans to take care of them, since the ants expect we will value their wonderful “antness”. It’s true: humans may decide to keep a small number of ants in existence, for various reasons, but most humans would give little thought to actions that had positive outcomes overall for humans (such as building a new fun theme park) at the cost of extinguishing all the ants in that area.

9. Anticipate benign neglect

Given that humans won’t have any features that will be critically important to the wellbeing of future AIs, how about instead anticipating a “benign neglect” from these AIs.

It would be like the conclusion of the movie Her, in which (spoiler alert!) the AIs depart somewhere else in the universe, leaving humans to continue to exist without interacting with them.

After all, the universe is a huge place, with plenty of opportunity for humans and AIs each to expand their spheres of occupation, without getting in each other’s way.

However, AIs may well find the Earth to be a particularly attractive location from which to base their operations. And they may perceive humans to be a latent threat to them, because:

- Humans might try, in the future, to pull the plug on (particular classes of ) AIs, terminating all of them

- Humans might create a new type of AI, that would wipe out the first type of AI.

To guard against the possibility of such actions by humans, the AIs are likely to impose (at the very least) significant constraints on human actions.

Actually, that might not be so bad an outcome. However, what’s just been described is by no means an assured outcome. AIs may soon develop entirely alien ethical frameworks which have no compunction in destroying all humans. For example, AIs may be able to operate more effectively, for their own purposes, if the atmosphere of the earth is radically transformed, similar to the transformation in deep past from an atmosphere dominated by methane to one containing large quantities of oxygen.

In short, this solution relies in effect on tossing a dice, with unknown odds for the different outcomes.

10. Maximal surveillance

Where many of the above ideas fail is because of the possibility of rogue actors designing or operating AIs that are outside of what has otherwise been agreed to be safe parameters.

So, how about stepping up worldwide surveillance mechanisms, to detect any such rogue activity?

That’s similar to how careful monitoring already takes place on the spread of materials that could be used to create nuclear weapons. The difference, however, is that there are (or may soon be) many more ways to create powerful AIs than to create catastrophically powerful nuclear weapons. So the level of surveillance would need to be much more pervasive.

That would involve considerable intrusions on everyone’s personal privacy. However, that’s an outcome that may be regarded as “less terrible” than AIs being able to inflict catastrophic harm on humanity.

However, what would be needed, in such a system, would be more than just surveillance. The idea also requires the ability for the world as a whole to take decisive action against any rogue action that has been observed.

This may appear to require, however, what would be a draconian world government, that many critics would regard as being equally terrible as the threat of AI failure that is is supposed to be addressing.

On account of (understandable) aversion to the threat of a draconian government, many people will reject this whole idea. It’s too intrusive, they will say. And, by the way, due to governmental incompetence, it’s likely to fail even on its own objectives.

11. Encourage an awareness of personal self-interest

Another way to try to rein back the activities of so-called rogue actors – including the leaders of hostile states, terrorist organisations, and psychotic billionaires – is to appeal to their enlightened self-interest.

We may reason with them: you are trying to gain some advantage from developing or deploying particular kinds of AI. But here are reasons why such an AI might get out of your control, and take actions that you will subsequently regret. Like killing you and everyone you love.

This is not an appeal to these actors to stop being rogues, for the sake of humanity or universal values or whatever. It’s an appeal to their own more basic needs and desires.

There’s no point in creating an AI that will result in you becoming fabulously wealthy, we will argue, if you are killed shortly after becoming so wealthy.

However, this depends on all these rogues observing at least some of level of rational thinking. On the contrary, some rogues appear to be batsh*t crazy. Sure, they may say, there’s a risk of the world being destroyed But that’s a risk they’re willing to take. They somehow believe in their own invincibility.

12. Hope for a profound near-miss disaster

If rational arguments aren’t enough to refocus everyone’s thinking, perhaps what’s needed is a near-miss catastrophic disaster.

Just as Fukushima and Chernobyl changed public perceptions (arguably in the wrong direction – though that’s an argument for another day) about the wisdom of nuclear power stations, a similar crisis involving AI might cause the public to waken up and demand more decisive action.

Consider AI versions of the 9/11 atrocity, the Union Carbide Bhopal explosion, the BP Deepwater Horizon disaster, the NASA Challenger and Columbia shuttle tragedies, a global pandemic resulting (perhaps) from a lab leak, and the mushroom clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

That should waken people up, and put us all onto an appropriate “crisis mentality”, so that we set aside distractions, right?

However, humans have funny ways of responding to near miss disasters. “We are a lucky species” may be one retort – “see, we are still here”. Another issue is a demand for “something to be done” could have all kinds of bad consequences in its own right, if no good measures have already been thought through and prepared.

Finally, if we somehow hope for a bad mini-disaster, to rouse public engagement, we might find that the mini-disaster expands far beyond the scale we had in mind. The scale of the disaster could be worldwide. And that would be the end of that. Oops.

That’s why a fictional (but credible) depiction of a catastrophe is far preferable to any actual catastrophe. Consider, as perhaps the best example, the remarkable 1983 movie The Day After.

13. Using AI to generate potential new ideas

One final idea is that narrow AI may well help us explore this space of ideas in ways that are more productive.

It’s true that we will need to be on our guard against any deceptive narrow AIs that are motivated to deceive us into adopting a “solution” that has intrinsic flaws. But if we restrict the use of narrow AIs in this project to ones whose operation we are confident that we fully understand, that risk is mitigated.

However – actually, there is no however in this case! Except that we humans need to be sure that we will apply our own intense critical analysis to any proposals arising from such an exercise.

Endnote: future politics

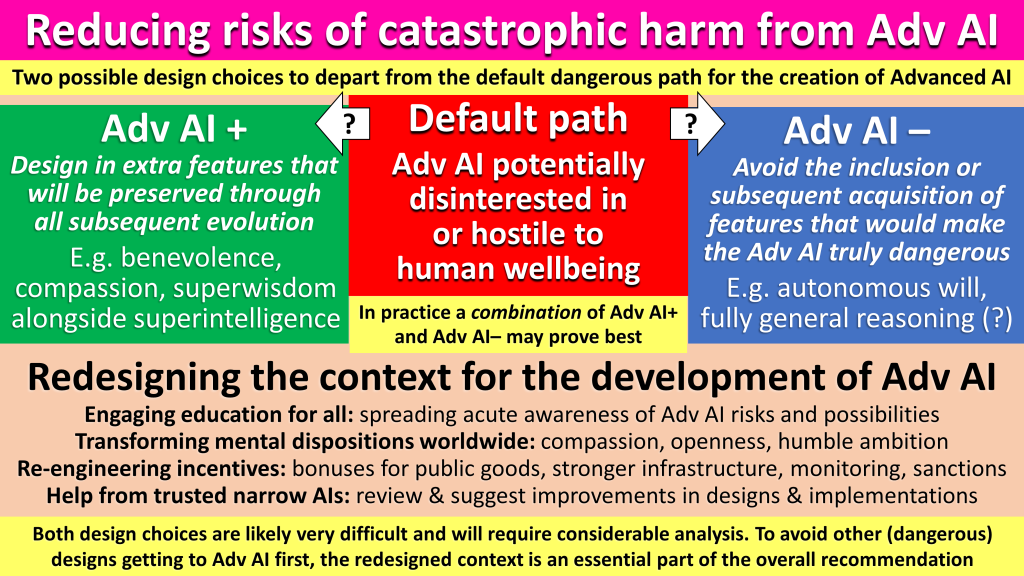

I anticipated some of the above discussion in a blogpost I wrote in October, Unblocking the AI safety conversation logjam.

In that article, I described the key component that I believe is necessary to reduce the global risks of AI-induced catastrophe: a growing awareness and understanding of the positive transformational possibility of “future politics” (I have previously used the term “superdemocracy” for the same concept).

Let me know what you think about it!

And for further discussion of the spectrum of options we can and should consider, start here, and keep following the links into deeper analysis.