On Tuesday last week I joined members of “The Big Potatoes” for a spirited discussion entitled “Automation Anxiety”. Participants became embroiled in questions such as:

- To what extent will increasingly capable automation (robots, software, and AI) displace humans from the workforce?

- To what extent should humans be anxious about this process?

The Big Potatoes website chose an image from the marvellously provocative Channel 4 drama series “Humans” to set the scene for the discussion:

“Closer to humans” than ever before, the fictional advertisement says, referring to humanoid robots with multiple capabilities. In the TV series, many humans became deeply distressed at the way their roles are being usurped by these new-fangled entities.

Back in the real world, many critics reject these worries. “We’ve heard it all before”, they assert. Every new wave of technological automation has caused employment disruption, yes, but it has also led to new types of employment. The new jobs created will compensate for the old ones destroyed, the critics say.

I see these critics as, most likely, profoundly mistaken. This time things are different. That’s because of the general purpose nature of ongoing improvements in the algorithms for automation. Machine learning algorithms that are developed with one set of skills in mind turn out to fit, reasonably straightforwardly, into other sets of skills as well.

The master algorithm

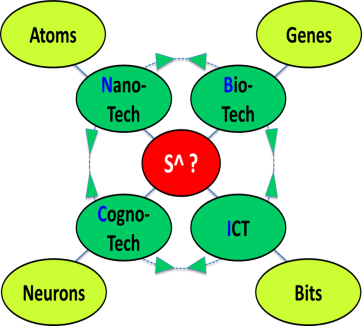

That argument is spelt out in the recent book “The master algorithm” by University of Washington professor of computer science and engineering Pedro Domingos.

The subtitle of that book refers to a “quest for the ultimate learning machine”. This ultimate learning machine can be contrasted with another universal machine, namely the universal Turing machine:

- The universal Turing machine accepts inputs and applies a given algorithm to compute corresponding outputs

- The universal learning machine accepts a set of corresponding input and output data, and makes the best possible task of inferring the algorithm that would obtain the outputs from the inputs.

For example, given sets of texts written in English, and matching texts written in French, the universal learning machine would infer an algorithm that will convert English into French. Given sets of biochemical reactions of various drugs on different cancers, the universal learning machine would infer an algorithm to suggest the best treatment for any given cancer.

As Domingos explains, there are currently five different “tribes” within the overall machine learning community. Each tribe has its separate origin, and also its own idea for the starting point of the (future) master algorithm:

- “Symbolists” have their origin in logic and philosophy; their core algorithm is “inverse deduction”

- “Connectionists” have their origin in neuroscience; their core algorithm is “back-propagation”

- “Evolutionaries” have their origin in evolutionary biology; their core algorithm is “genetic programming”

- “Bayesians” have their origin in statistics; their core algorithm is “probabilistic inference”

- “Analogizers” have their origin in psychology; their core algorithm is “kernel machines”.

(See slide 6 of this Slideshare presentation. Indeed, take the time to view the full presentation. Better again, read Domingos’ entire book.)

What’s likely to happen over the next decade, or two, is that a single master algorithm will emerge that unifies all the above approaches – and, thereby, delivers great power. It will be similar to the progress made by physics as the fundamental force of natures have gradually been unified into a single theory.

And as that unification progresses, more and more occupations will be transformed, more quickly than people generally expect. Technological unemployment will rise and rise, as software embodying the master algorithm handles tasks previously thought outside the scope of automation.

Incidentally, Domingos has set out some ambitious goals for what his book will accomplish:

The goal is to do for data science what “Chaos” [by James Gleick] did for complexity theory, or “The Selfish Gene” [by Richard Dawkins] for evolutionary game theory: introduce the essential ideas to a broader audience, in an entertaining and accessible way, and outline the field’s rich history, connections to other fields, and implications.

Now that everyone is using machine learning and big data, and they’re in the media every day, I think there’s a crying need for a book like this. Data science is too important to be left just to us experts! Everyone – citizens, consumers, managers, policymakers – should have a basic understanding of what goes on inside the magic black box that turns data into predictions.

People who comment about the likely impact of automation on employment would do particularly well to educate themselves about the ideas covered by Domingos.

Rise of the robots

There’s a second reason why “this time it’s different” as regards the impact of new waves of automation on the employment market. This factor is the accelerating pace of technological change. As more areas of industry become subject to digitisation, they become, at the same time, subject to automation.

That’s one of the arguments made by perhaps the best writer so far on technological unemployment, Martin Ford. Ford’s recent book “Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future” builds ably on what previous writers have said.

Here’s a sample of review comments about Ford’s book:

Lucid, comprehensive and unafraid to grapple fairly with those who dispute Ford’s basic thesis, Rise of the Robots is an indispensable contribution to a long-running argument.

—Los Angeles TimesIf The Second Machine Age was last year’s tech-economy title of choice, this book may be 2015’s equivalent.

—Financial Times, Summer books 2015, Business, Andrew Hill[Ford’s] a careful and thoughtful writer who relies on ample evidence, clear reasoning, and lucid economic analysis. In other words, it’s entirely possible that he’s right.

—Daily BeastSurveying all the fields now being affected by automation, Ford makes a compelling case that this is an historic disruption—a fundamental shift from most tasks being performed by humans to one where most tasks are done by machines.

—Fast CompanyWell-researched and disturbingly persuasive.

—Financial TimesMartin Ford has thrust himself into the center of the debate over AI, big data, and the future of the economy with a shrewd look at the forces shaping our lives and work. As an entrepreneur pioneering many of the trends he uncovers, he speaks with special credibility, insight, and verve. Business people, policy makers, and professionals of all sorts should read this book right away—before the ‘bots steal their jobs. Ford gives us a roadmap to the future.

—Kenneth Cukier, Data Editor for the Economist and co-author of Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and ThinkEver since the Luddites, pessimists have believed that technology would destroy jobs. So far they have been wrong. Martin Ford shows with great clarity why today’s automated technology will be much more destructive of jobs than previous technological innovation. This is a book that everyone concerned with the future of work must read.

—Lord Robert Skidelsky, Emeritus Professor of Political Economy at the University of Warwick, co-author of How Much Is Enough?: Money and the Good Life and author of the three-volume biography of John Maynard Keynes

If you’re still not convinced, I recommend that you listen to this audio podcast of a recent event at London’s RSA, addressed by Ford.

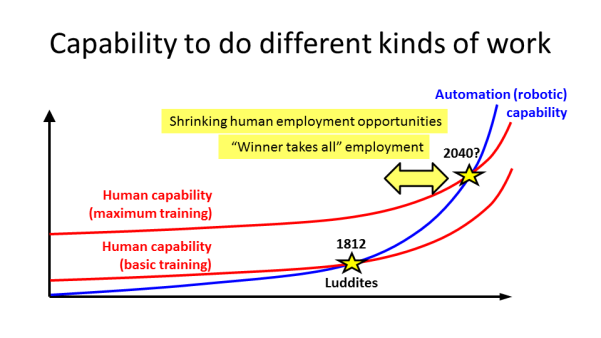

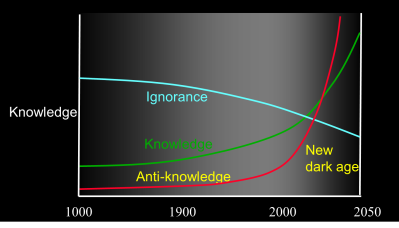

I summarise the takeaway message in this picture, taken from one of my Delta Wisdom workshop presentations:

- Yes, humans can retrain over time, to learn new skills, in readiness for new occupations when their former employment has been displaced by automation

- However, the speed of improvement of the capabilities of automation will increasingly exceed that of humans

- Coupled with the general purpose nature of these capabilities, it means that, conceivably, from some time around 2040, very few humans will be able to find paid work.

A worked example: a site carpenter

During the Big Potatoes debate on Tuesday, I pressed the participants to name an occupation that would definitely be safe from incursion by robots and automation. What jobs, if any, will robots never be able to do?

One suggestion that came back was “site carpenter”. In this thinking, unfinished buildings are too complex, and too difficult for robots to navigate. Robots who try to make their way through these buildings, to tackle carpentry tasks, will likely fall down. Or assuming they don’t fall down, how will they cope with finding out that the reality in the building often varies sharply from the official specification? These poor robots will try to perform some carpentry task, but will get stymied when items are in different places from where they’re supposed to be. Or have different tolerances. Or alternatives have been used. Etc. Such systems are too messy for robots to compute.

My answer is as follows. Yes, present-day robots currently often do fall down. Critics seem to find this hilarious. But this is pretty similar to the fact that young children often fall down, while learning to walk. Or novice skateboarders often fall down, when unfamiliar with this mode of transport. However, robots will learn fast. One example is shown in this video, of the “Atlas” humanoid robot from Boston Dynamics (now part of Google):

As for robots being able to deal with uncertainty and surprises, I’m frankly struck by the naivety of this question. Of course software can deal with uncertainty. Software calculates courses of action statistically and probabilistically, the whole time. When software encounters information at variance from what it previously expected, it can adjust its planned course of action. Indeed, it can take the same kinds of steps that a human would consider – forming new hypotheses, and, when needed, checking back with management for confirmation.

The question is a reminder to me that the software and AI community need to do a much better job to communicate the current capabilities of their field, and the likely improvements ahead.

What does it mean to be human?

For me, the most interesting part of Tuesday’s discussion was when it turned to the following questions:

- Should these changes be welcomed, rather than feared?

- What will these forthcoming changes imply for our conception of what it means to be human?

To my mind, technological unemployment will force us to rethink some of the fundamentals of the “protestant work ethic” that permeates society. That ethic has played a decisive positive role for the last few centuries, but that doesn’t mean we should remain under its spell indefinitely.

If we can change our conceptions, and if we can manage the resulting social transition, the outcome could be extremely positive.

Some of these topics were aired at a conference in New York City on 29th September: “The World Summit on Technological Unemployment”, that was run by Jim Clark’s World Technology Network.

One of the many speakers at that conference, Scott Santens, has kindly made his slides available, here. Alongside many graphs on the increasing “winner takes all” nature of modern employment (in which productivity increases but median income declines), Santens offers a different way of thinking about how humans should be spending their time:

We are not facing a future without work. We are facing a future without jobs.

There is a huge difference between the two, and we must start seeing the difference, and making the difference more clear to each other.

In his blogpost “Jobs, Work, and Universal Basic Income”, Santens continues the argument as follows:

When you hate what you do as a job, you are definitely getting paid in return for doing it. But when you love what you do as a job or as unpaid work, you’re only able to do it because of somehow earning sufficient income to enable you to do it.

Put another way, extrinsically motivated work is work done before or after an expected payment. It’s an exchange. Intrinsically motivated work is work only made possible by sufficient access to money. It’s a gift.

The difference between these two forms of work cannot be overstated…

Traditionally speaking, most of the work going on around us is only considered work, if one gets paid to do it. Are you a parent? Sorry, that’s not work. Are you in paid childcare? Congratulations, that’s work. Are you an open source programmer? Sorry, that’s not work. Are you a paid software engineer? Congratulations, that’s work…

What enables this transformation would be some variant of a “basic income guarantee” – a concept that is introduced in the slides by Santens, and also in the above-mentioned book by Martin Ford. You can hear Ford discuss this option in his RSA podcast, where he ably handles a large number of questions from the audience.

What I found particularly interesting from that podcast was a comment made by Anthony Painter, the RSA’s Director of Policy and Strategy who chaired the event:

The RSA will be advocating support for Basic Income… in response to Technological Unemployment.

(This comment comes about 2/3 of the way through the podcast.)

To be clear, I recognise that there will be many difficulties in any transition from the present economic situation to one in which a universal basic income applies. That transition is going to be highly challenging to manage. But these problems of transition are a far better problem to have, than dealing with the consequences of vastly increased unpaid unemployment and social alienation.

Life is being redefined

Just in case you’re still tempted to dismiss the above scenarios as some kind of irresponsible fantasy, there’s one more resource you might like to consult. It’s by Janna Q. Anderson, Professor of Communications at Elon University, and is an extended write-up of a presentation I heard her deliver at the World Future 2015 conference in San Francisco this July.

You can find Anderson’s article here. It starts as follows:

The Robot Takeover is Already Here

The machines that replace us do not have to have superintelligence to execute a takeover with overwhelming impacts. They must merely extend as they have been, rapidly becoming more and more instrumental in our essential systems.

It’s the Algorithm Age. In the next few years humans in most positions in the world of work will be nearly 100 percent replaced by or partnered with smart software and robots —’black box’ invisible algorithm-driven tools. It is that which we cannot see that we should question, challenge and even fear the most. Algorithms are driving the world. We are information. Everything is code. We are becoming dependent upon and even merging with our machines. Advancing the rights of the individual in this vast, complex network is difficult and crucial.

The article is described as being a “45 minute read”. In turn, it contains numerous links, so you could spend lots longer following the resulting ideas. In view of the momentous consequences of the trends being discussed, that could prove to be a good use of your time.

By way of summary, I’ll pull out a few sentences from the middle of the article:

One thing is certain: Employment, as it is currently defined, is already extremely unstable and today many of the people who live a life of abundance are not making nearly enough of an effort yet to fully share what they could with those who do not…

It’s not just education that is in need of an overhaul. A primary concern in this future is the reinvention of humans’ own perceptions of human value…

[Another] thing is certain: Life is being redefined.

Who controls the robots?

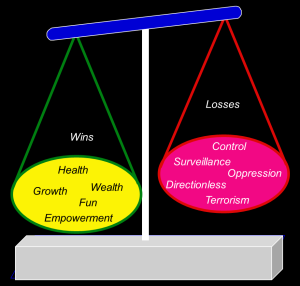

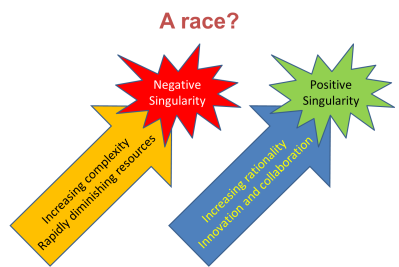

Despite the occasional certainty in this field (as just listed above, extracted from the article by Janna Anderson), there remains a great deal of uncertainty. I share with my Big Potatoes colleagues the viewpoint that technology does not determine social responses. The question of which future scenario will unfold isn’t just a question of cheer-leading (if you’re an optimist) or cowering (if you’re a pessimist). It’s a question of choice and action.

That’s a theme I’ll be addressing next Sunday, 18th October, at a lunchtime session of the 2015 Battle of Ideas. The session is entitled “Man vs machine: Who controls the robots”.

Here’s how the session is described:

From Metropolis through to recent hit film Ex Machina, concerns about intelligent robots enslaving humanity are a sci-fi staple. Yet recent headlines suggest the reality is catching up with the cultural imagination. The World Economic Forum in Davos earlier this year hosted a serious debate around the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, organised by the NGO Human Rights Watch to oppose the rise of drones and other examples of lethal autonomous warfare. Moreover, those expressing the most vocal concerns around the march of the robots can hardly be dismissed as Luddites: the Elon-Musk funded and MIT-backed Future of Life Institute sparked significant debate on artificial intelligence (AI) by publishing an open letter signed by many of the world’s leading technologists and calling for robust guidelines on AI research to ‘avoid potential pitfalls’. Stephen Hawking, one of the signatories, has even warned that advancing robotics could ‘spell the end of the human race’.

On the other hand, few technophiles doubt the enormous potential benefits of intelligent robotics: from robot nurses capable of tending to the elderly and sick through to the labour-saving benefits of smart machines performing complex and repetitive tasks. Indeed, radical ‘transhumanists’ openly welcome the possibility of technological singularity, where AI will become so advanced that it can far exceed the limitations of human intelligence and imagination. Yet, despite regular (and invariably overstated) claims that a computer has managed to pass the Turing Test, many remain sceptical about the prospect of a significant power shift between man and machine in the near future…

Why has this aspect of robotic development seemingly caught the imagination of even experts in the field, when even the most remarkable developments still remain relatively modest? Are these concerns about the rise of the robots simply a high-tech twist on Frankenstein’s monster, or do recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence pose new ethical questions? Is the question more about from who builds robots and why, rather than what they can actually do? Does the debate reflect the sheer ambition of technologists in creating smart machines or a deeper philosophical crisis in what it means to be human?

As you can imagine, I’ll be taking serious issue with the above claim, from the session description, that progress with robots will “remain relatively modest”. However, I’ll be arguing for strong focus on questions of control.

It’s not just a question of whether it’s humans or robots that end up in control of the planet. There’s a critical preliminary question as to which groupings and systems of humans end up controlling the evolution of robots, software, and automation. Should we leave this control to market mechanisms, aided by investment from the military? Or should we exert a more general human control of this process?

In line with my recent essay “Four political futures: which will you choose?”, I’ll be arguing for a technoprogressive approach to control, rather than a technolibertarian one.

I wait with interest to find out how much this viewpoint will be shared by the other speakers at this session:

- Dr Robert Clowes – chair, Mind & Cognition Group, Nova Institute of Philosophy, Lisbon University; chair, Lisbon Salon

- Professor Steve Fuller – Auguste Comte Chair in Social Epistemology, University of Warwick

- Timandra Harkness – journalist, writer & broadcaster; presenter, The Singularity & other BBC Radio 4 programmes; writer & performer, science-based comedy shows, including BrainSex

- Martyn Perks (who is chairing the discussion) – digital business consultant and writer; co-author, Big Potatoes: the London manifesto for innovation.