Three essential leadership skills in life involve starting projects, adjusting projects, and stopping projects:

- Not being dominated by “analysis paralysis” or “always waiting for a better time to begin” or “expecting someone else to make things happen” – but being able to start a project with a promising initial direction, giving it a sufficient push to generate movement and wider interest

- Not being dominated by the momentum that builds up around a project, giving it an apparently fixed trajectory, fixed tools, fixed processes, and fixed targets – but being able to pivot the project into a new form, based on key insights that have emerged as the project has been running

- Not being dominated by excess feelings of loyalty to a project, or by guilt about costs that have already been sunk into that project – but being able to stop projects that, on reflection, ought to have lower priority than others which have a bigger likelihood of real positive impact.

When I talk about the value of being able to stop projects, it’s not just bad projects that I have in mind as needing to be stopped. I have in mind the need to occasionally stop projects for which we retain warm feelings – projects which are still good projects, and which may in some ways be personal favourites of ours. However, these projects have lost the ability to become great projects, and if we keep giving them attention, we’re taking resources away from places where they would more likely produce wonderful results.

After all, there are only so many hours in a day. Leadership is more than better time management – finding ways to apply our best selves for a larger number of minutes each day. Leadership is about choices – choices, as I said, about what to start, what to adjust, and what to stop. Done right, the result is that the time we invest will have better consequences. Done wrong, the result is that we never quite reach critical mass, despite lots of personal heroics.

I’m pretty good at time management, but now I need to make some choices. I need to cut back, in order to move forward better. That means saying goodbye to some of my favourite projects, and shutting them down.

First things first

The phrase “move forward better” begs the question: forward to where?

There’s no point in (as I said) “having a bigger likelihood of real positive impact” if that impact is in an area that, on reflection, isn’t important.

As Stephen Covey warned us in his 1988 book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People,

It’s incredibly easy to get caught up in an activity trap, in the busy-ness of life, to work harder and harder at climbing the ladder of success only to discover it’s leaning against the wrong wall.

Hence Covey’s emphasis on the leadership habit of “Start with the end in mind”:

Management is efficiency in climbing the ladder of success; leadership determines whether the ladder is leaning against the right wall.

For me, the “end in mind” can be described as sustainable superabundance for all.

That’s a theme I’ve often talked about over the years. It’s even the subject of an entire book I wrote and published in 2019.

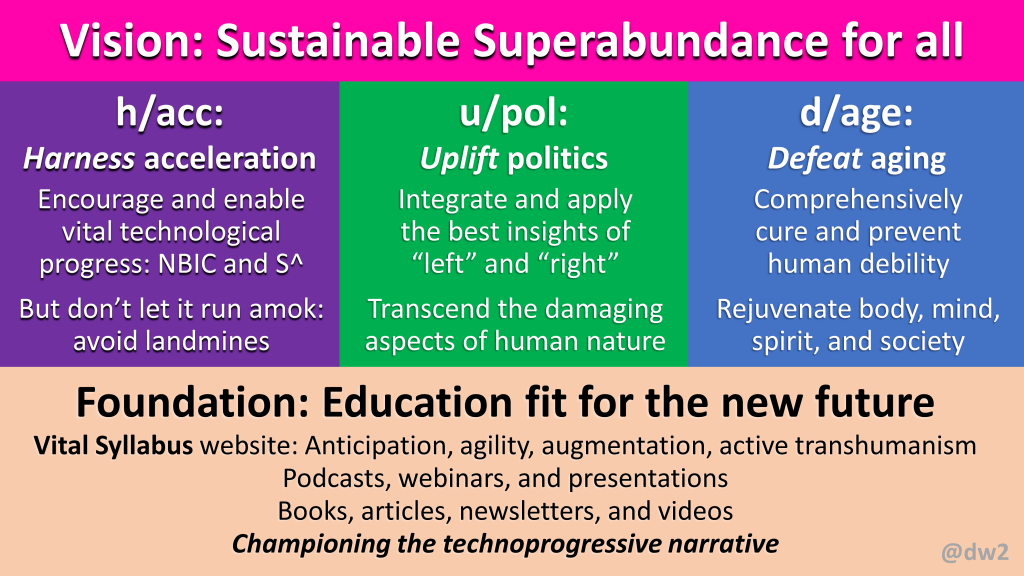

That’s what I’ve written at the top of the following chart, which I’ve created as a guide for myself regarding which projects I should prioritise (and which I should deprioritise):

Three pillars and a core foundation

In that chart, the “end in mind” is supported by three pillars: a pillar of responsible power, a pillar of collaborative growth, and a pillar of blue skies achievement. For these pillars, I’m using the shorthand, respectively, of h/acc, u/pol, and d/age:

- h/acc: Harness acceleration

- Encourage and enable vital technological progress

- NBIC (nanotech, biotech, infotech, and cognotech) and S^ (progress toward a positive AI singularity)

- But don’t let it run amok: avoid landmines (such as an AI-induced catastrophe)

- u/pol: Uplift politics

- Integrate and apply the best insights of “left” and “right”

- Transcend the damaging aspects of human nature

- d/age: Defeat aging

- Comprehensively cure and prevent human debility

- Rejuvenate body, mind, spirit, and society

These pillars are in turn supported by a foundation:

- Education fit for the new future

- The Vital Syllabus website, covering skills that can be grouped as anticipation, agility, augmentation, and active transhumanism

- Podcasts, webinars, and presentations

- Books, articles, newsletters, and videos

- Championing the technoprogressive narrative

Back in the real world

Switching back from big picture thinking to real-world activities, here are some of the main ways I expect to be spending my time in the next 12-24 months – activities that are in close alignment with that big picture vision:

- In my role as Executive Director of the LEV (Longevity Escape Velocity) Foundation, I’m fortunate to be assisting a wonderful team of individuals assembled by visionary biomedical gerontologist Aubrey de Grey with the declared mission to “cure and prevent age-related disease”

- In my role as Foresight Advisor to the leadership team of SingularityNET, headed by visionary AGI scientist Ben Goertzel, I contribute to various key tasks, including helping to shape aspects of the forthcoming BGI (Beneficial AGI) Summit and contributing to Mindplex

- In partnership with renowned author Calum Chace, I co-host the London Futurists Podcast, which continues to receive lots of inspiring feedback

- I take part in projects from time to time on potential political initiatives to improve the governance of disruptive technologies, including work with the Millennium Project on scenarios for governing the transition from narrow AI to general AI, and work with the OmniFuturists on solutions to the Economic Singularity

- I take part in projects from time to time with the leadership of the IEET (Institute of Ethics and Emerging Technologies), where I retain a seat on their board, and Humanity+, where I have an advisory role, to clarify and develop the technoprogressive narrative and the practice of active transhumanism

- When I judge the audience and topic to be a good fit, I offer keynote presentations, workshops, change facilitation services, and tailored reports, via my consultancy and publishing company Delta Wisdom

- As chair of the London Futurists community, from time to time I publish newsletters, organise online webinars or real-world gatherings, or partner with other groups to help co-create events – such as Transvision Utrecht 2024 which is taking place in Holland in January

- I maintain a very useful set of material on the Transpolitica website – tagline “Anticipating tomorrow’s politics” – including significant extracts of many of my books (e.g. The Singularity Principles and Vital Foresight)

- I’ll be improving the selection and arrangement of educational content on the Vital Syllabus site, and building a team of people who actively contribute feedback and new material for that site.

Any sensible person would say – and I am sometimes tempted to agree – that such a list of (count them) nine demanding activities is too much to put on any one individual’s plate. However, there are many synergies between these activities, which makes things easier. And I can draw on four decades of relevant experience, plus a large network of people who can offer support from time to time.

In other words, all nine of these activities remain on my list of “great” activities. None are being dropped – although some will happen less frequently than before. (For example, I used to schedule a London Futurists webinar almost every week; don’t expect that frequency to resume any time soon.)

However, a number of my other activities do need to be cut back.

Goodbye party politics

You might have noticed that many of the activities I’ve described above involve politics. Indeed, the shorthand “u/pol” occupies a central position in the big picture chart I shared.

But what’s not present is party politics.

Back in January 2015, I was one of a team of around half a dozen transhumanist enthusiasts based in the UK who created the Transhumanist Party UK (sometimes known as TPUK). Later that year, that party obtained formal registration from the UK electoral commission. In principle, the party could stand candidates in UK elections.

I initially took the role of Treasurer, and after several departures from the founding team, I’ve had two spells as Party Leader. In the most recent spell, I undertook one renaming (from Transhumanist Party UK to Transhumanist UK) and then another – to Future Surge.

I’m very fond of Future Surge. There’s a lot of inspired material on that website.

For a while, I even contemplated running on the Future Surge banner as a candidate for the London Mayor in the mayoral elections in May 2024. That would, I thought, generate a lot of publicity. Here’s a video from Transvision 2021 in Madrid where I set out those ideas.

But that would be a huge undertaking – one not compatible with many of the activities I’ve listed earlier.

It would also be a financially expensive undertaking, and require a kind of skill that’s not a good match for me personally.

In any case, there’s a powerful argument that the best way for a pressure group to alter politics, in countries like the UK where elections take place under the archaic first-past-the-post system – is to find allies within existing parties.

That way, instead of debating what the TPUK policies should be on a wide spectrum of topics – policies needed if TPUK were to be a “real” political party – we could concentrate just on highlighting the ideas that we held in common – the technoprogressive narrative and active transhumanism.

Thus rather than having a Transhumanist Party (capital T and capital P), there should be outreach activities to potential allies of transhumanist causes in the Conservatives, Labour, LibDems, Greens, Scottish Nationalists, and so on.

For a long time, I had in mind the value of a two-pronged approach: education to existing political figures, alongside a disruptive new political party.

Well, I’m cutting back to just one of these prongs.

That’s a decision I’ve repeatedly delayed taking. However, it’s now time to act.

Closing down Future Surge

I’ll be cancelling all recurring payments made by people who have signed up as members (“subscribers”) of the party. These funds have paid for a number of software services over the years, including websites such as H+Pedia (I’ll say more about H+Pedia shortly).

Anyone kind enough to want to continue making small annual (or in some cases monthly) donations will be able to sign up instead as a financial supporter of Vital Syllabus.

I’ll formally deregister the party from the UK Electoral Commission. (Remaining registered costs money and requires regular paperwork.)

Before I close down the Future Surge website, I’ll copy selected parts of it to an archive location – probably on Transpolitica.

Future Surge also has a Discord server, where a number of members have been sharing ideas and conversations related to the goals of the party. With advance warning of the pending shutdown of the Future Surge Discord, a number of these members are relocating to a newly created Discord, called “Future Fireside”.

A new owner for H+Pedia?

Another project which has long been a favourite of mine is H+Pedia. As is declared on the H+Pedia home page:

H+Pedia is a project to spread accurate, accessible, non-sensational information about transhumanism, futurism, radical life extension and other emerging technologies, and their potential collective impact on humanity.

H+Pedia uses the same software as Wikipedia, to host material that, in an ideal world, ought to be included in Wikipedia, but which Wikipedia admins deem as failing to meet their criteria for notability, relevance, independence, and so on.

If I look at H+Pedia today, with its 4,915 pages of articles, I see a mixture of quality:

- A number of the pages have excellent material, that does not exist elsewhere in the same form

- Many of the pages are mediocre, and cover material that is less central to the purposes of H+Pedia

- Even some of the good pages are in need of significant updates following the passage of time.

If I had more time myself, I would probably remove around 50% of the existing pages, as well as updating many of the others.

But that is a challenge I am going to leave to other people to (perhaps) pick up.

The hosting of H+Pedia on SiteGround costs slightly over UK £400 per year. (These payments have been covered from funds from TPUK.) The next payment is due in June 2024.

If a suitable new owner of H+Pedia comes forward before June 2024, I will happily transfer ownership details to them, and they can evolve the project as they best see fit.

Otherwise, I will shut the project down.

Either way, I plan to copy content from a number of the H+Pedia pages to Transpolitica.

Moving forward better

In conclusion: I’ll be sad to bid farewell to both Future Surge and H+Pedia.

But as in the saying, you’ve got to give up to go up.