Here’s an argument with a conclusion that may surprise you.

The topic is how to reduce the risks of existential or catastrophic outcomes from forthcoming new generations of AI.

The conclusion is these risks can be reduced by funding some key laboratory experiments involving middle-aged mice – experiments that have a good probability of demonstrating a significant increase in the healthspan and lifespan of these mice.

These experiments have a name: RMR2, which stands for Robust Mouse Rejuvenation, phase 2. If you’re impatient, you can read about these experiments here, on the website of LEVF, the organisation where I have a part-time role as Executive Director.

For clarity: LEVF stands for Longevity Escape Velocity Foundation. I describe LEVF’s work in more detail in the Appendix to this article. But first, let’s return to the topic of the risks posed by future AI systems.

The hypothesis

I am advancing a sociotechnical hypothesis: that perceived hopelessness about aging materially increases tolerance for AI risk, and that credible progress on aging reduces that tolerance.

An underlying driver of greater risk

There are many different opinions about the extent and nature of the risks that new generations of AI may create. However, despite this diversity of viewpoint, there is general consensus on one point: As the development and deployment of new generations of AI becomes more hurried and more reckless, the risk of undesirable outcomes also increases. The more haste, the more danger.

Now, one factor that encourages people to hurry to develop and deploy AI in potentially reckless ways (shortcutting safety evaluations and other design audits), is their fear that progress in solving aging is proceeding too slowly. Perceiving few signs of any solution to aging via conventional methods, they yearn for what they hope may be a “hail Mary” pass – an impetuous attempt to accelerate the arrival of superintelligent AI.

Accordingly, I’ve often heard people making an argument like this: Yes, there is a nonzero risk of mass deaths arising from superintelligent AI that is badly aligned and uncontrollable. But there’s a 100% chance of death from aging in the absence of major progress with AI.

Advocates of this point of view accept the first risk in order to have a chance of avoiding the second risk.

Even when not consciously articulated, these trade-offs can shape behaviour. People may have in mind that every single day of delay in building superintelligent AI causes around 100,000 extra deaths from aging. Such a large quantity of unnecessary deaths is horrific. Given that pressure, why worry about hypothetical risks from AI?

(Note: The desire to solve aging as quickly as possible isn’t the only driver of AI developer recklessness. Profit, geopolitics, and personal prestige play roles too, for different people. But my case is that aging-related urgency is a non-trivial contributor to over-hasty development.)

A third option?

One counter to the above trade-off argument is to point out that it makes a false binary. There are more than two choices. A very important third choice is to solve aging by creative extensions of biotechnology and AI that already exist. That approach won’t need the extraordinary disruption of superintelligent AI.

But many advocates of rushing as fast as possible towards superintelligent AI dismiss the chance of anything like a “business as usual” solution to aging. They think the idea of a third option is an illusion. Decades of previous effort have delivered almost nothing of practical utility, they claim. No person has reached the age of 120 this century. Calorie restriction, known since the 1930s, is still the best intervention to increase the lives of normal middle-aged laboratory mice. Biological metabolism is far too complicated for unaided human scientists to work out how to alter it to avoid aging. And so on.

It’s those considerations that push more people to the following conclusion: The most reliable way to solve aging is, first, to create a superintelligent AI, and then to let this AI solve aging on our behalf.

With that conclusion in their mind, people then feel strong psychological and social pressure to turn a blind eye to any arguments that the creation of such an AI has a significant risk of killing vast numbers of people worldwide.

Challenging the spiral of pessimism

Can we break this spiral of pessimism and unwise risk tolerance?

Yes! By demonstrating how today’s AI systems, coupled with smart laboratory experiments on normal middle aged laboratory mice, can indeed break records for the extension of healthspan and lifespan. These experiments will apply combinations of damage-repair interventions such as senescent cell clearance, partial cellular reprogramming, cross-link breaking, and the infusion of exosomes, among other treatments.

This demonstration will interrupt the vicious cycle of negativity about current biotech research into solving aging. It will also show that repairing the low-level damage which constitutes biological aging can be effective even without any attempt to remodel core biological metabolism.

Indeed, what’s preventing faster progress in solving aging isn’t the lack of a more capable AI. It’s the lack of key experimental data as to the outcomes of multiple different damage-repair therapies being applied in parallel. That all-important data is what LEVF’s RMR programme will generate, provided sufficient funding is made available.

Bear in mind that AI gains its intelligence from relevant high quality training data. The training of DeepMind’s AlphaFold depended on information about the 3D structure of many proteins that was painstakingly assembled by pioneering human researchers over five decades – an initiative presciently started in 1971 by Helen Berman. Again, the remarkable breakthroughs in image recognition of AlexNet in 2012, which catalysed the entire field of deep neural networks, depended on the vast ImageNet database of labelled images assembled by Stanford’s Fei Fei Li and numerous Amazon Turk contractors.

These datasets didn’t just accelerate progress – they changed what the field believed was possible.

(Of course, data alone is not sufficient – but history shows that without the right data, even the best algorithms stall.)

It’s likely to be the same with solving aging. Data created by the RMR programme can be analysed by a combination of smart humans aided by today’s state-of-the-art AI. The output will be a design for a package of interventions that have a good chance to provide comprehensive high-quality low-cost age-reversal therapies for humans.

As that pathway becomes clearer, it will remove a strong incentive for many AI developers to adopt and tolerate methods that are far too dangerous and haphazard. Instead, we can anticipate a very welcome change in trajectory, toward reliably trustworthy safe AI development.

A complement not a replacement

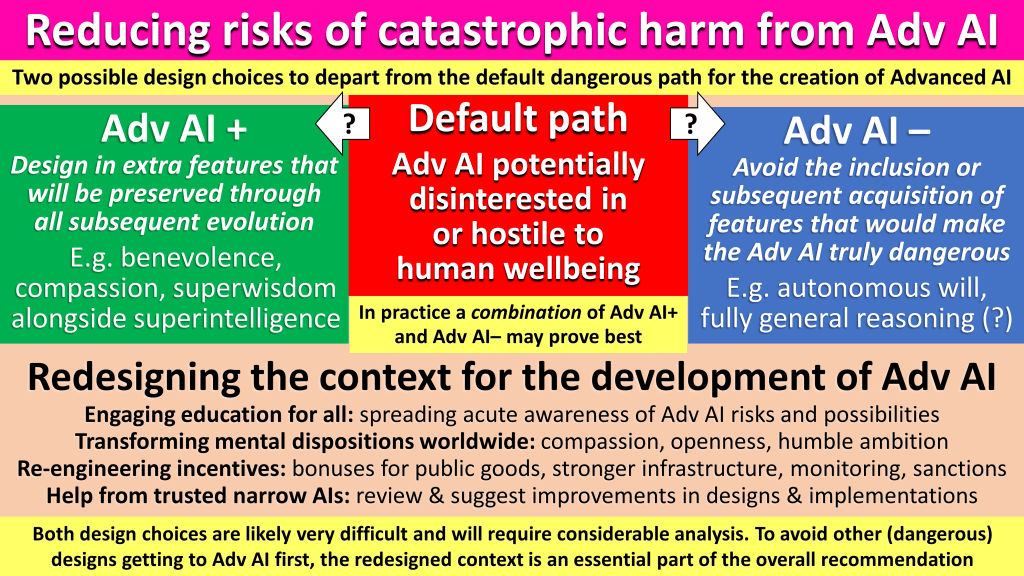

Let me offer a short aside to alignment researchers, governance advocates, and “slow down AI” proponents.

To be clear, my advocacy for funding to be allocated in support of potential breakthrough healthy longevity projects like RMR is a complement (not a replacement) for ongoing work in favour of AI alignment, AI regulation, and selective AI pauses.

I’m not arguing for any of these activities to be reduced. Reducing the risks of AI catastrophe will require progress along a wide spectrum of different activities.

But I emphasise healthy longevity projects as part of a very necessary change in public mood towards the governance of AI.

If that mood is driven primarily by fear and is expressed as calls for sacrifices – “these are things we have to stop doing” – that will be an uphill battle. The campaign is likely to gain more momentum when the messages are “Safe AI can truly enhance human flourishing” and “here are things we can and should be doing more”.

Tackling two major risk factors in parallel

In summary: When people support the funding of LEVF, for the RMR2 project, they’re addressing not one but two potential causes of death of themselves and everyone they care about:

- The likelihood of death from an age-related condition

- The likelihood of death from misaligned or uncontrolled advanced AI.

If you find this argument compelling, one concrete way to act is to visit the LEVF donation page.

And if you happen to know any particularly wealthy people, who likewise care about all the misery that could follow from either of these risks, kindly nudge them towards that page too.

Appendix

Here are some more details of how success with RMR will ignite major changes in science funding, in turn leading to profound worldwide humanitarian benefit.

70% of all deaths around the world are caused by age-related diseases – diseases that become increasingly likely and increasingly deadly the longer people live.

The root cause of these age-related diseases is the gradual accumulation of various types of cellular and biomolecular damage.

An increasing number of damage-repair interventions have been discovered, proposed, and studied, which each have the ability to reverse aspects of this damage.

Applying a sufficient number of these interventions in parallel has the potential to significantly extend both lifespan and healthspan, even when started as late as middle age.

Most of the world is unnecessarily sceptical about the potential of such combination treatments. The way minds can be changed is to demonstrate significant results in middle-aged mice – Robust Mouse Rejuvenation (RMR):

- A successful result will involve a statistically significant number of ordinary middle-aged mice (aged 18 months, out of an average lifespan for these mice of 30 months) and will at least double their mean and maximum (90% decile) remaining lifespan.

- Note: In human terms, this would be the equivalent of applying treatments to a group of people aged 50, who ordinarily would on average live to the age of around 80, with the result that their mean lifespan would instead become 110.

LEVF anticipates that demonstrating RMR will trigger a multi-step change in social priorities, leading to a grand “war on aging” with much greater resources applied to translating these results from mice to larger, longer-lived mammals, such as dogs, primates, and humans.

Importantly, even partial success – strong additive effects without full lifespan doubling – would still constitute decisive evidence against the claim that aging is intractable without superintelligence.

Between 2023 and 2025, LEVF has already conducted an initial project (RMR1), involving four different anti-aging interventions. As anticipated, the RMR1 interventions were additive in effect, though the set of only four interventions was insufficient to attain RMR. A pilot phase of a second, larger project (RMR2) is now underway, that applies important learnings from RMR1:

- For RMR2, a larger number of different treatments will be applied (8 instead of 4), covering a wider range of types of cellular and biomolecular damage

- RMR2 will introduce new damage-repair interventions that have been individually validated since RMR1 started

- For best effect, each damage repair treatment will likely need to be applied more than once in the remaining lifespan of each mouse

- The experiment will determine which combinations of treatments are, regrettably, antagonistic, and which are synergistic.

The demonstration of RMR will have a huge impact on the scientific community that researches aging and rejuvenation:

- Many researchers in this community are presently preoccupied with trying to understand the precise causal pathways that create various kinds of biological damage, with a view to somehow altering these pathways

- However, organismal metabolism is extraordinarily complicated, and many problematic side-effects arise from attempts to alter pathways to avoid producing damage

- For this reason, the community contains a lot of scepticism that aging can be brought under comprehensive control any time soon

- In contrast, LEVF emphasises that interventions to repair or reverse damage can be understood and applied without needing to understand how the damage is created in the first place: damage removal is easier than slowing down damage creation

- For example, there is no need to endlessly debate whether aging should be understood from an evolutionary point of view or an entropic point of view; nor whether to adopt so-called “holist” or “reductionist” approaches; instead, what can (and should) happen is to develop interventions that remove or repair different types of damage

- LEVF therefore champions an engineering approach, similar to how vaccines were developed and deployed with wide success long before the full complexity of the immune system was understood

- Even among researchers sympathetic to the damage-repair approach, there is significant pessimism about the pace of progress – on account of extrapolating from the modest life-extension results obtained by applying damage repair interventions on a single basis

- In contrast, LEVF anticipates that, once a sufficient number of interventions is applied, in a suitable combination, gains in healthspan and lifespan will be much more dramatic

- RMR, therefore, will give many researchers a good reason to switch from pessimism to stronger optimism

- This will lead to many more researchers carrying out variations of the RMR experiments in different settings, with different animals.

Translation from rejuvenation in mice to rejuvenation in humans won’t be entirely straightforward, as humans accumulate different kinds of damage in different ways from mice – and accordingly experience chronic age-related diseases in different proportions. However, consider two possible processes:

- Modifying metabolism, with all its variety and complexity, to avoid producing damage, whilst still having all the required positive products

- Augmenting current biological interactions with new, damage-repair interventions.

Of these two processes, the latter is likely to translate more easily from one species (such as mice) to another (such as humans).

Once RMR is achieved – either by RMR2, or, more likely, in a follow-up project such as RMR3, completed by the end of 2030 – a cascade of effects can be anticipated. Dates cannot be predicted with any certainty, but here is one possible scenario, with some illustrative order-of-magnitude projections:

- From 2026 to 2032, a twenty-fold increase will take place in the amount of funding applied globally each year to the R&D of anti-aging damage-repair interventions. In parallel, any talk of “aging being natural therefore medicine should avoid trying to fix it” will, thankfully, become a very minority opinion

- By 2035, affordable treatments will be routinely available around the world, which when applied to people in good general health but with biological age measured as 60 or more, will result in their effective ages being reduced by at least 5 years, as assessed by comprehensive tests that cover all aspects of human vitality

- By 2040, the set of treatments that are routinely available at that time will reduce these comprehensive measures of biological age by at least 10 years

- Also by 2040, the amount of money spent on healthcare services around the world will be less than in 2026 (adjusted for inflation). That’s because there will be much less need for expensive treatments of people suffering from chronic age-related conditions.

Accordingly, a significant investment in RMR2 at the start of 2026 could catalyse enormous humanitarian benefits downstream.