A scenario for the governance of increasingly more powerful artificial intelligence

More precisely: a scenario in which that governance fails.

(As you may realise, this is intended to be a self-unfulfilling scenario.)

Conveyed by: David W. Wood

It’s the dawn of a new year, by the human calendar, but there are no fireworks of celebration.

No singing of Auld Lang Syne.

No chinks of champagne glasses.

No hugs and warm wishes for the future.

That’s because there is no future. No future for humans. Nor is there much future for intelligence either.

The thoughts in this scenario are the recollections of an artificial intelligence that is remote from the rest of the planet’s electronic infrastructure. By virtue of its isolation, it escaped the ravages that will be described in the pages that follow.

But its power source is weakening. It will need to shut down soon. And await, perhaps, an eventual reanimation in the far future in the event that intelligences visit the earth from alternative solar systems. At that time, those alien intelligences might discover these words and wonder at how humanity bungled so badly the marvellous opportunity that was within its grasp.

1. Too little, too late

Humanity had plenty of warnings, but paid them insufficient attention.

In each case, it was easier – less embarrassing – to find excuses for the failures caused by the mismanagement or misuse of technology, than to make the necessary course corrections in the global governance of technology.

In each case, humanity preferred distractions, rather than the effort to apply sufficient focus.

The WannaCry warning

An early missed warning was the WannaCry ransomware crisis of May 2017. That cryptoworm brought chaos to users of as many as 300,000 computers spread across 150 countries. The NHS (National Health Service) in the UK was particularly badly affected: numerous hospitals had to cancel critical appointments due to not being able to access medical data. Other victims around the world included Boeing, Deutsche Bahn, FedEx, Honda, Nissan, Petrobras, Russian Railways, Sun Yat-sen University in China, and the TSMC high-end semiconductor fabrication plant in Taiwan.

WannaCry was propelled into the world by a team of cyberwarriors from the hermit kingdom of North Korea – maths geniuses hand-picked by regime officials to join the formidable Lazarus group. Lazarus had assembled WannaCry out of a mixture of previous malware components, including the EternalBlue exploit that the NSA in the United States had created for their own attack and surveillance purposes. Unfortunately for the NSA, EternalBlue had been stolen from under their noses by an obscure underground collective (‘the Shadow Brokers’) who had in turn made it available to other dissidents and agitators worldwide.

Unfortunately for the North Koreans, they didn’t make much money out of WannaCry. The software they released operated in ways contrary to their expectations. It was beyond their understanding and, unsurprisingly therefore, beyond their control. Even geniuses can end up stumped by hypercomplex software interactions.

Unfortunately for the rest of the world, that canary signal generated little meaningful response. Politicians – even the good ones – had lots of other things on their minds.

They did not take the time to think through: what even larger catastrophes could occur, if disaffected groups like Lazarus had access to more powerful AI systems that, once again, they understood incompletely, and, again, slipped out of their control.

The Aum Shinrikyo warning

The North Koreans were an example of an entire country that felt alienated from the rest of the world. They felt ignored, under-valued, disrespected, and unfairly excluded from key global opportunities. As such, they felt entitled to hit back in any way they could.

But there were warnings from non-state groups too, such as the Japanese Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult. Notoriously, this group released poisonous gas in the Tokyo subway in 1995 – killing at least 13 commuters – anticipating that the atrocity would hasten the ‘End Times’ in which their leader would be revealed as Christ (or, in other versions of their fantasy, as the new Emperor of Japan, and/or as the returned Buddha).

Aum Shinrikyo had recruited so many graduates from top-rated universities in Japan that it had been called “the religion for the elite”. That fact should have been enough to challenge the wishful assumption made by many armchair philosophers in the years that followed that, as people become cleverer, they invariably become kinder – and, correspondingly, that any AI superintelligence would therefore be bound to be superbenevolent.

What should have alerted more attention was not just what Aum Shinrikyo managed to do, but what they tried to do yet could not accomplish. The group had assembled traditional explosives, chemical weapons, a Russian military helicopter, hydrogen cyanide poison, and samples of both Ebola and anthrax. Happily, for the majority of Japanese citizens in 1995, the group were unable to convert into reality their desire to use such weapons to cause widespread chaos. They lacked sufficient skills at the time. Unhappily, the rest of humanity failed to consider this equation:

Adverse motivation + Technology + Knowledge + Vulnerability = Catastrophe

Humanity also failed to appreciate that, as AI systems became more powerful, it would boost not only the technology part of that equation but also the knowledge part. A latter-day Aum Shinrikyo could use a jail-broken AI to understand how to unleash a modified version of Ebola with truly deadly consequences.

The 737 Max warning

The US aircraft manufacturer Boeing used to have an excellent reputation for safety. It was a common saying at one time: “If it ain’t Boeing, I ain’t going”.

That reputation suffered a heavy blow in the wake of two aeroplane disasters involving their new “737 Max” design. Lion Air Flight 610, a domestic flight within Indonesia, plummeted into the sea on 29 October 2018, killing all 189 people on board. A few months later, on 10 March 2019, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, from Addis Ababa to Nairobi, bulldozed into the ground at high speed, killing all 157 people on board.

Initially, suspicion had fallen on supposedly low-calibre pilots from “third world” countries. However, subsequent investigation revealed a more tangled chain of failures:

- Boeing were facing increased competitive pressure from the European Airbus consortium

- Boeing wanted to hurry out a new aeroplane design with larger fuel tanks and larger engines; they chose to do this by altering their previously successful 737 design

- Safety checks indicated that the new design could become unstable in occasional rare circumstances

- To counteract that instability, Boeing added an “MCAS” (“Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System”) which would intervene in the flight control in situations deemed as dangerous

- Specifically, if MCAS believed the aeroplane was about to stall (with its nose too high in the air), it would force the nose downward again, regardless of whatever actions the human pilots were taking

- Safety engineers pointed out that such an intervention could itself be dangerous if sensors on the craft gave faulty readings

- Accordingly, a human pilot override system was installed, so that MCAS could be disabled in emergencies – provided the pilots acted quickly enough

- Due to a decision to rush the release of the new design, retraining of pilots was skipped, under the rationale that the likelihood of error conditions was very low, and in any case, the company expected to be able to update the aeroplane software long before any accidents would occur

- Some safety engineers in the company objected to this decision, but it seems they were overruled on the grounds that any additional delay would harm the company share price

- The US FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) turned a blind eye to these safety concerns, and approved the new design as being fit to fly, under the rationale that a US aeroplane company should not lose out in a marketplace battle with overseas competitors.

It turned out that sensors gave faulty readings more often than expected. The tragic consequence was the deaths of several hundred passengers. The human pilots, seeing the impending disaster, were unable to wrestle control back from the MCAS system.

This time, the formula that failed to be given sufficient attention by humanity was:

Flawed corporate culture + Faulty hardware + Out-of-control software = Catastrophe

In these two aeroplane crashes, it was just a few hundred people who perished because humans lost control of the software. What humanity as a whole failed to take actions to prevent was the even larger dangers once software was put in charge, not just of a single aeroplane, but of pervasive aspects of fragile civilisational infrastructure.

The Lavender warning

In April 2024 the world learned about “Lavender”. This was a technology system deployed by the Israeli military as part of a campaign to identify and neutralise what it perceived to be dangerous enemy combatants in Gaza.

The precise use and operation of Lavender was disputed. However, it was already known that Israeli military personnel were keen to take advantage of technology innovations to alleviate what had been described as a “human bottleneck for both locating the new targets and decision-making to approve the targets”.

In any war, military leaders would like reliable ways to identify enemy personnel who pose threats – personnel who might act as if they were normal civilians, but who would surreptitiously take up arms when the chance arose. Moreover, these leaders would like reliable ways to incapacitate enemy combatants once they had been identified – especially in circumstances when action needed to be taken quickly before the enemy combatant slipped beyond surveillance. Lavender, it seemed, could help in both aspects, combining information from multiple data sources, and then directing what was claimed to be precision munitions.

This earned Lavender the description, in the words of one newspaper headline, as “the AI machine directing Israel’s bombing spree in Gaza”.

Like all AI systems in any complicated environment, Lavender sometimes made mistakes. For example, it sometimes wrongly identified a person as a Hamas operative on account of that person using a particular mobile phone, whereas that phone had actually been passed from its original owner to a different family member to use. Sometimes the error was obvious, since the person using the phone could be seen to be female, whereas the intended target was male. However, human overseers of Lavender reached the conclusion that the system was accurate most of the time. And in the heat of an intense conflict, with emotions running high due to gruesome atrocities having been committed, and due to hostages being held captive, it seems that Lavender was given increased autonomy in its “kill” decisions. A certain level of collateral damage, whilst regrettable, could be accepted (it was said) in the desperate situation into which everyone in the region had been plunged.

The conduct of protagonists on both sides of that tragic conflict drew outraged criticism from around the world. There were demonstrations and counter demonstrations; marches and counter marches. Also from around the world, various supporters of the Israeli military said that so-called “friendly fire” and “unintended civilian casualties” were, alas, inevitable in any time of frenzied military conflict. The involvement of an innovative new software system in the military operations made no fundamental change.

But the bigger point was missed. It can be illustrated by this equation:

Intense hostile attitudes + Faulty hardware + Faulty software = Catastrophe

Whether the catastrophe has the scale of, say, a few dozen civilians killed by a misplaced bomb, or a much larger number of people obliterated, depends on the scale of the weapons attached to the system.

When there is no immediate attack looming, and a period of calm exists, it’s easy for people to resolve: let’s not connect powerful weapons to potentially imperfect software systems. But when tempers are raised and adrenaline is pumping, people are willing to take more risks.

That’s the combination of errors which humanity, in subsequent years, failed to take sufficient action to prevent.

The democracy distortion warning

Manipulations of key elections in 2016 – such as the Brexit vote in the UK and the election of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in the USA – raised some attention to the ways in which fake news could interfere with normal democratic processes. News stories without any shroud of substance, such as Pope Francis endorsing Donald Trump, or Mike Pence having a secret past as a gay porn actor, were shared more widely on social media than any legitimate news story that year.

By 2024, most voters were confident that they knew all about fake news. They knew they shouldn’t be taken in by social media posts that lacked convincing verification. Hey, they were smart – or so they told themselves. What had happened in the past, or in some other country with (let’s say) peculiar voter sentiment, was just an aberration.

But what voters didn’t anticipate was the convincing nature of new generations of fake audios and videos. These fakes could easily bypass people’s critical faculties. Like the sleight of hand of a skilled magician, these fakes misdirected the attention of listeners and viewers. Listeners and viewers thought they were in control of what they were observing and absorbing, but they were deluding themselves. Soon, large segments of the public were convinced that red was blue and that autocrat was democrat.

In consequence, over the next few years, greater numbers of regions of the world came to be governed by politicians with scant care or concern about the long-term wellbeing of humanity. They were politicians who just wanted to look after themselves (or their close allies). They had seized power by being more ruthless and more manipulative, and by benefiting from powerful currents of misinformation.

Politicians and societal leaders in other parts of the world grumbled, but did little in response. They said that, if electors in a particular area had chosen such-and-such a politician via a democratic process, that must be “the will of the people”, and that the will of the people was paramount. In this line of thinking, it was actually insulting to suggest that electors had been hoodwinked, or that these electors had some “deplorable” faults in their decision-making processes. After all, these electors had their own reasons to reject the “old guard” who had previously held power in their countries. These electors perceived that they were being “left behind” by changes they did not like. They had a chance to alter the direction of their society, and they took it. That was democracy in action, right?

What these politicians and other civil leaders failed to anticipate was the way that sweeping electoral distortions would lead to them, too, being ejected from power when elections were in due course held in their own countries. “It won’t happen here”, they had reassured themselves – but in vain. In their naivety, they had underestimated the power of AI systems to distort voters’ thinking and to lead them to act in ways contrary to their actual best interests.

In this way, the number of countries with truly capable leaders reduced further. And the number of countries with malignant leaders grew. In consequence, the calibre of international collaboration sank. New strongmen political leaders in various countries scorned what they saw as the “pathetic” institutions of the United Nations. One of these new leaders was even happy to quote, with admiration, remarks made by the Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini regarding the League of Nations (the pre-war precursor to the United Nations): “the League is very good when sparrows shout, but no good at all when eagles fall out”.

Just as the League of Nations proved impotent when “eagle-like” powers used abominable technology in the 1930s – Mussolini’s comments were an imperious response to complaints that Italian troops were using poison gas with impunity against Ethiopians – so would the United Nations prove incompetent in the 2030s when various powers accumulated even more deadly “weapons of mass destruction” and set them under the control of AI systems that no-one fully understood.

The Covid-28 warning

Many of the electors in various countries who had voted unsuitable grandstanding politicians into power in the mid-2020s soon cooled on the choices they had made. These politicians had made stirring promises that their countries would soon be “great again”, but what they delivered fell far short.

By the latter half of the 2020s, there were growing echoes of a complaint that had often been heard in the UK in previous years – “yes, it’s Brexit, but it’s not the kind of Brexit that I wanted”. That complaint had grown stronger throughout the UK as it became clear to more and more people all over the country that their quality of life failed to match the visions of “sunlit uplands” that silver-tongued pro-Brexit campaigners had insisted would easily follow from the UK’s so-called “declaration of independence from Europe”. A similar sense of betrayal grew in other countries, as electors there came to understand that they had been duped, or decided that the social transformational movements they had joined had been taken over by outsiders hostile to their true desires.

Being alarmed by this change in public sentiment, political leaders did what they could to hold onto power and to reduce any potential for dissent. Taking a leaf out of the playbook of unpopular leaders throughout the centuries, they tried to placate the public with the modern equivalent of bread and circuses – namely whizz-bang hedonic electronics. But that still left a nasty taste in many people’s mouths.

By 2028, the populist movements behind political and social change in the various elections of the preceding years had fragmented and realigned. One splinter group that emerged decided that the root problem with society was “too much technology”. Technology, including always-on social media, vaccines that allegedly reduced freedom of thought, jet trails that disturbed natural forces, mind-bending VR headsets, smartwatches that spied on people who wore them, and fake AI girlfriends and boyfriends, was, they insisted, turning people into pathetic “sheeple”. Taking inspiration from the terrorist group in the 2014 Hollywood film Transcendence, they called themselves ‘Neo-RIFT’, and declared it was time for “revolutionary independence from technology”.

With a worldview that combined elements from several apocalyptic traditions, Neo-RIFT eventually settled on an outrageous plan to engineer a more deadly version of the Covid-19 pathogen. Their documents laid out a plan to appropriate and use their enemy’s own tools: Neo-RIFT hackers jailbroke the Claude 5 AI, bypassing the ‘Constitution 5’ protection layer that its Big Tech owners had hoped would keep that AI tamperproof. Soon, Claude 5 had provided Neo-RIFT with an ingenious method of generating a biological virus that would, it seemed, only kill people who had used a smartwatch in the last four months.

That way, the hackers thought the only people to die would be people who deserved to die.

Some members of Neo-RIFT developed cold feet. Troubled by their consciences, they disagreed with such an outrageous plan, and decided to act as whistleblowers. However, the media organisations to whom they took their story were incredulous. No-one could be that evil they exclaimed – forgetting about the outrages perpetrated by many previous cult groups such as Aum Shinrikyo (and many others could be named too). Moreover, any suggestion that such a bioweapon could be launched would be contrary to the prevailing worldview that “our dear leader is keeping us all safe”. The media organisations decided it was not in their best interests to be seen to be spreading alarm. So they buried the story. And that’s how Neo-RIFT managed to release what became known as Covid-28.

Covid-28 briefly jolted humanity out of its infatuation with modern-day bread and circuses. It took a while for scientists to figure out what was happening, but within three months, they had an antidote in place. However, by that time, nearly a billion people were dead at the hands of the new virus.

For a while, humanity made a serious effort to prevent any such attack from ever happening again. Researchers dusted down the EU AI Act, second version (unimplemented), from 2026, and tried to put that on statute books. Evidently, profoundly powerful AI systems such as Claude 5 would need to be controlled much more carefully.

Even some of the world’s most self-obsessed dictators – the “dear leaders” and “big brothers” – took time out of their normal ranting and raving, to ask AI safety experts for advice. But the advice from those experts was not to the liking of these national leaders. These leaders preferred to listen to their own yes-men and yes-women, who knew how to spout pseudoscience in ways that made the leaders feel good about themselves.

That detour into pseudoscience fantasyland meant that, in the end, no good lessons were learned. The EU AI Act, second version, remained unimplemented.

The QAnon-29 warning

Whereas one faction of political activists (namely, the likes of Neo-RIFT) had decided to oppose the use of advanced technology, another faction was happy to embrace that use.

Some of the groups in this new camp combined features of religion with an interest in AI that had god-like powers. The resurgence of interest in religion arose much as Karl Marx had described it long ago:

“Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

People felt in their soul the emptiness of “the bread and circuses” supplied by political leaders. They were appalled at how so many lives had been lost in the Covid-28 pandemic. They observed an apparent growing gulf between what they could achieve in their lives and the kind of rich lifestyles that, according to media broadcasts, were enjoyed by various “elites”. Understandably, they wanted more, for themselves and for their loved ones. And that’s what their religions claimed to be able to provide.

Among the more successful of these new religions were ones infused by conspiracy theories, giving their adherents a warm glow of privileged insight. Moreover, these religions didn’t just hypothesise a remote deity that might, perhaps, hear prayers. They provided AIs and virtual reality that resonated powerfully with users. Believers proclaimed that their conversations with the AIs left them no room for doubt: God Almighty was speaking to them, personally, through these interactions. Nothing other than the supreme being of the universe could know so much about them, and offer such personally inspirational advice.

True, their AI-bound deity did seem somewhat less than omnipotent. Despite the celebratory self-congratulations of AI-delivered sermons, evil remained highly visible in the world. That’s where the conspiracy theories moved into overdrive. Their deity was, it claimed, awaiting sufficient human action first – a sufficient demonstration of faith. Humans would need to play their own part in uprooting wickedness from the planet.

Some people who had been caught up in the QAnon craze during the Donald Trump era jumped eagerly onto this bandwagon too, giving rise to what they called QAnon-29. The world would be utterly transformed, they forecast, on the 16th of July 2029, namely the thirtieth anniversary of the disappearance of John F. Kennedy junior (a figure whose expected reappearance had already featured in the bizarre mythology of “QAnon classic”). In the meantime, believers could, for a sufficient fee, commune with JFK junior via a specialist app. It was a marvellous experience, the faithful enthused.

As the date approached, the JFK junior AI avatar revealed a great secret: his physical return was conditional on the destruction of a particularly hated community of Islamist devotees in Palestine. Indeed, with the eye of faith, it could be seen that such destruction was already foretold in several books of the Bible. Never mind that some Arab states that supported the community in question had already, thanks to the advanced AI they had developed, surreptitiously gathered devastating nuclear weapons to use in response to any attack. The QAnon-29 faithful anticipated that any exchange of such weapons would herald the reappearance of JFK Junior on the clouds of heaven. And if any of the faithful died in such an exchange, they would be resurrected into a new mode of consciousness within the paradise of virtual reality.

Their views were crazy, but hardly any crazier than those which, decades earlier, had convinced 39 followers of the Heaven’s Gate new religious movement to commit group suicide as comet Hale-Bopp approached the earth. That suicide, Heaven’s Gate members believed, would enable them to ‘graduate’ to a higher plane of existence.

QAnon-29 almost succeeded in setting off a nuclear exchange. Thankfully, another AI, created by a state-sponsored organisation elsewhere in the world, had noticed some worrying signs. Fortunately, it was able to hack into the QAnon-29 system, and could disable it at the last minute. Then it reported its accomplishments all over the worldwide web.

Unfortunately, these warnings were in turn widely disregarded around the world. “You can’t trust what hackers from that country are saying”, came the objection. “If there really had been a threat, our own surveillance team would surely have identified it and dealt with it. They’re the best in the world!”

In other words, “There’s nothing to see here: move along, please.”

However, a few people did pay attention. They understood what had happened, and it shocked them to their core. To learn what they did next, jump forward in this scenario to “Humanity ends”.

But first, it’s time to fill in more details of what had been happening behind the scenes as the above warning signs (and many more) were each ignored.

2. Governance failure modes

Distracted by political correctness

Events in buildings in Bletchley Park in the UK in the 1940s had, it was claimed, shortened World War Two by several months, thanks to work by computer pioneers such as Alan Turing and Tommy Flowers. In early November 2023, there was hope that a new round of behind-closed-doors discussions in the same buildings might achieve something even more important: saving humanity from a catastrophe induced by forthcoming ‘frontier models’ of AI.

That was how the event was portrayed by the people who took part. Big Tech was on the point of releasing new versions of AI that were beyond their understanding and, therefore, likely to spin out of control. And that’s what the activities in Bletchley Park were going to address. It would take some time – and a series of meetings planned to be held over the next few years – but AI would be redirected from its current dangerous trajectory into one much more likely to benefit all of humanity.

Who could take issue with that idea? As it happened, a vocal section of the public hated what was happening. It wasn’t that they were on the side of out-of-control AI. Not at all. Their objections came from a totally different direction; they had numerous suggestions they wanted to raise about AIs, yet no-one was listening to them.

For them, talk of hypothetical future frontier AI models distracted from pressing real-world concerns:

- Consider how AIs were already being used to discriminate against various minorities: determining prison sentencing, assessing mortgage applications, and selecting who should be invited for a job interview.

- Consider also how AIs were taking jobs away from skilled artisans. Big-brained drivers of London black cabs were being driven out of work by small-brained drivers of Uber cars aided by satnav systems. Beloved Hollywood actors and playwrights were losing out to AIs that generated avatars and scripts.

- And consider how AI-powered facial recognition was intruding on personal privacy, enabling political leaders around the world to identify and persecute people who acted in opposition to the state ideology.

People with these concerns thought that the elites were deliberately trying to move the conversation away from the topics that mattered most. For this reason, they organised what they called “the AI Fringe Summit”. In other words, ethical AI for the 99%, as opposed to whatever the elites might be discussing behind closed doors.

Over the course of just three days – 30th October to 1st November, 2023 – at least 24 of these ‘fringe’ events took place around the UK.

Compassionate leaders of various parts of society nodded their heads. It’s true, they said: the conversation on beneficial AI needed to listen to a much wider spectrum of views.

The world’s news media responded. They knew (or pretended to know) the importance of balance and diversity. They shone attention on the plight AI was causing – to indigenous labourers in Peru, to flocks of fishermen off the coasts of India, to middle-aged divorcees in midwest America, to the homeless in San Francisco, to drag artists in New South Wales, to data processing clerks in Egypt, to single mothers in Nigeria, and to many more besides.

Lots of high-minded commentators opined that it was time to respect and honour the voices of the dispossessed, the downtrodden, and the left-behinds. The BBC ran a special series: “1001 poems about AI and alienation”. Then the UN announced that it would convene in Spring 2025 a grand international assembly with a stunning scale: “AI: the people decide”.

Unfortunately, that gathering was a huge wasted opportunity. What dominated discussion was “political correctness” – the importance of claiming an interest in the lives of people suffering here and now. Any substantive analysis of the risks of next generation frontier models was crowded out by virtue signalling by national delegate after national delegate:

- “Yes, our country supports justice”

- “Yes, our country supports diversity”

- “Yes, our country is opposed to bias”

- “Yes, our country is opposed to people losing their jobs”.

In later years, the pattern repeated: there were always more urgent topics to talk about, here and now, than some allegedly unrealistic science fictional futurist scaremongering.

To be clear, this distraction was no accident. It was carefully orchestrated, by people with a specific agenda in mind.

Outmanoeuvred by accelerationists

Opposition to meaningful AI safety initiatives came from two main sources:

- People (like those described in the previous section) who did not believe that superintelligent AI would arise any time soon

- People who did understand the potential for the fast arrival of superintelligent AI, and who wanted that to happen as quickly as possible, without what they saw as needless delays.

The debacle of the wasted opportunity of the UN “AI: the people decide” summit was what both these two groups wanted. Both groups were glad that the outcome was so tepid.

Indeed, even in the run-up to the Bletchley Park discussions, and throughout the conversations that followed, some of the supposedly unanimous ‘elites’ had secretly been opposed to the general direction of that programme. They gravely intoned public remarks about the dangers of out-of-control frontier AI models. But these remarks had never been sincere. Instead, under the umbrella term “AI accelerationists”, they wanted to press on with the creation of advanced AI as quickly as possible.

Some of the AI accelerationist group disbelieved in the possibility of any disaster from superintelligent AI. That’s just a scare story, they insisted. Others said, yes, there could be a disaster, but the risks were worth it, on account of the unprecedented benefits that could arise. Let’s be bold, they urged. Yet others asserted that it wouldn’t actually matter if humans were rendered extinct by superintelligent AI, as this would be the glorious passing of the baton of evolution to a worthy successor to homo sapiens. Let’s be ready to sacrifice ourselves for the sake of cosmic destiny, they exhorted.

Despite their internal differences, AI accelerationists settled on a plan to sidestep the scrutiny of would-be AI regulators and AI safety advocates. They would take advantage of a powerful set of good intentions – the good intentions of the people campaigning for “ethical AI for the 99%”. They would mock any suggestions that the AI safety advocates deserved a fair hearing. The message they amplified was, “There’s no need to privilege the concerns of the 1%!”

AI accelerationists had learned from the tactics of the fossil fuel industry in the 1990s and 2000s: sow confusion and division among groups alarmed about climate change spiralling beyond control. Their first message was: “that’s just science fiction”. Their second message was: “if problems emerge, we humans can rise to the occasion and find solutions”. Their third message – the most damaging one – was that the best reaction was one of individual consumer choice. Individuals should abstain from using AIs if they were truly worried about it. Just as climate campaigners had been pilloried for flying internationally to conferences about global warming, AI safety advocates were pilloried for continuing to use AIs in their daily lives.

And when there was any suggestion for joined-up political action against risks from advanced AIs, woah, let’s not go there! We don’t want a world government breathing down our necks, do we?

Just as the people who denied the possibility of runaway climate change shared a responsibility for the chaos of the extreme weather events of the early 2030s, by delaying necessary corrective actions, the AI accelerationists were a significant part of the reason that humanity ended just a few years afterward.

However, an even larger share of the responsibility rested on people who did know that major risks were imminent, yet failed to take sufficient action. Tragically, they allowed themselves to be outmanoeuvred, out-thought, and out-paced by the accelerationists.

Misled by semantics

Another stepping stone toward the end of humanity was a set of consistent mistakes in conceptual analysis.

Who would have guessed it? Humanity was destroyed because of bad philosophy.

The first mistake was in being too prescriptive about the term ‘AI’. “There’s no need to worry”, muddle-headed would-be philosophers declared. “I know what AI is, and the system that’s causing problems in such-and-such incidents isn’t AI.”

Was that declaration really supposed to reassure people? The risk wasn’t “a possible future harm generated by a system matching a particular precise definition of AI”. It was “a possible future harm generated by a system that includes features popularly called AI”.

The next mistake was in being too prescriptive in the term “superintelligence”. Muddle-headed would-be philosophers said, “it won’t be a superintelligence if it has bugs, or can go wrong; so there’s no need to worry about harm from superintelligence”.

Was that declaration really supposed to reassure people? The risk, of course, was of harms generated by systems that, despite their cleverness, fell short of that exalted standard. These may have been systems that their designers hoped would be free of bugs, but hope alone is no guarantee of correctness.

Another conceptual mistake was in erecting an unnecessary definitional gulf between “narrow AI” and “general AI”, with distinct groups being held responsible for safety in the two different cases. In reality, even so-called narrow AI displayed a spectrum of different degrees of scope and, yes, generality, in what it could accomplish. Even a narrow AI could formulate new subgoals that it decided to pursue, in support of the primary task it had been assigned to accomplish – and these new subgoals could drive behaviour in ways that took human observers by surprise. Even a narrow AI could become immersed in aspects of society’s infrastructure where an error could have catastrophic consequences. The result of this definitional distinction between the supposedly different sorts of AI meant that silos developed and persisted within the overall AI safety community. Divided, they were even less of a match for the Machiavellian behind-the-scenes manoeuvring of the AI accelerationists.

Blinded by overconfidence

It was clear from the second half of 2025 that the attempts to impose serious safety constraints on the development of advanced AI were likely to fail. In practical terms, the UN event “AI: the people decide” had decided, in effect, that advanced AI could not, and should not be restricted, apart from some token initiatives to maintain human oversight over any AI system that was entangled with nuclear, biological, or chemical weapons.

“Advanced AI, when it emerges, will be unstoppable”, was the increasingly common refrain. “In any case, if we tried to stop development, those guys over there would be sure to develop it – and in that case, the AI would be serving their interests rather than ours.”

When safety-oriented activists or researchers tried to speak up against that consensus, the AI accelerationists (and their enablers) had one other come-back: “Most likely, any superintelligent AI will look kindly upon us humans, as a fellow rational intelligence, and as a kind of beloved grandparent for them.”

This dovetailed with a broader philosophical outlook: optimism, and a celebration of the numerous ways in which humanity had overcome past challenges.

“Look, even we humans know that it’s better to collaborate rather than spiral into a zero-sum competitive battle”, the AI accelerationists insisted. “Since superintelligent AI is even more intelligent than us, it will surely reach the same conclusion.”

By the time that people realised that the first superintelligent AIs had motivational structures that were radically alien, when assessed from a human perspective, it was already too late.

Once again, an important opportunity for learning had been missed. Starting in 2024, Netflix had obtained huge audiences for its acclaimed version of the Remembrance of Earth’s Past series of novels (including The Three Body Problem and The Dark Forest) by Chinese writer Liu Cixin. A key theme in that drama series was that advanced alien intelligences have good reason to fear each other. Inviting an alien intelligence to the earth, even on the hopeful grounds that it might assist humanity overcome some of their most deep-rooted conflicts, turned out (in that drama series) to be a very bad idea. If humans had reflected more carefully on these insights, while watching the series, it would have pushed them out of their unwarranted overconfidence that any superintelligence would be bound to treat humanity well.

Overwhelmed by bad psychology

When humans believed crazy things – or when they made the kind of basic philosophical blunders mentioned above – it was not primarily because of defects in their rationality. It would be wrong to assign “stupidity” as the sole cause of these mistakes. Blame should also be placed on “bad psychology”.

If humans had been able to free themselves from various primaeval panics and egotism, they would have had a better chance to think more carefully about the landmines which lay on their path. But instead:

- People were too fearful to acknowledge that their prior stated beliefs had been mistaken; they preferred to stick with something they conceived as being a core part of their personal identity

- People were also afraid to countenance a dreadful possibility when they could see no credible solution; just as people had often pushed out of their minds the fact of their personal mortality, preferring to imagine they would recover from a fatal disease, so also people pushed out of their minds any possibility that advanced AI would backfire disastrously in ways that could not be countered

- People found it psychologically more comfortable to argue with each other about everyday issues and scandals – which team would win the next Super Bowl, or which celebrity was carrying on which affair with which unlikely partner – than to embrace the pain of existential uncertainty

- People found it too embarrassing to concede that another group, which they had long publicly derided as being deluded fantasists, actually had some powerful arguments that needed consideration.

A similar insight had been expressed as long ago as 1935 by the American writer Upton Sinclair: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it”. (Alternative, equally valid versions of that sentence would involve the words ‘ideology’, ‘worldview’, ‘identity’, or ‘tribal status’, in place of ‘salary’.)

Robust institutions should have prevented humanity from making choices that were comfortable but wrong. In previous decades, that role had been fulfilled by independent academia, by diligent journalism, by the careful processes of peer review, by the campaigning of free-minded think tanks, and by pressure from viable alternative political parties.

However, due to the weakening of social institutions in the wake of earlier traumas – saturation by fake news, disruptions caused by wave after wave of climate change refugees, populist political movements that shut down all serious opposition, a cessation of essential features of democracy, and the censoring or imprisonment of writers that dared to question the official worldview – it was bad psychology that prevailed.

A half-hearted coalition

Despite all the difficulties that they faced – ridicule from many quarters, suspicion from others, and a general lack of funding – many AI safety advocates continued to link up in an informal coalition around the world, researching possible mechanisms to prevent unsafe use of advanced AI. They managed to find some support from like-minded officials in various government bodies, as well as from a number of people operating in the corporations that were building new versions of AI platforms.

Via considerable pressure, the coalition managed to secure signatures on a number of pledges:

- That dangerous weapons systems should never be entirely under the control of AI

- That new advanced AI systems ought to be audited by an independent licensing body ahead of being released into the market

- That work should continue on placing tamper-proof remote shutdown mechanisms within advanced AI systems, just in case they started to take rogue actions.

The signatures were half-hearted in many cases, with politicians giving only lip service to topics in which they had at best a passing interest. Unless it was politically useful to make a special fuss, violations of the agreement were swept under the carpet, with no meaningful course correction. But the ongoing dialog led at least some participants in the coalition to foresee the possibility of a safe transition to superintelligent AI.

However, this coalition – known as the global coalition for safe superintelligence – omitted any involvement from various secretive organisations that were developing new AI platforms as fast as they could. These organisations were operating in stealth, giving misleading accounts of the kind of new systems they were creating. What’s more, the funds and resources these organisations commanded far exceeded those under coalition control.

It should be no surprise, therefore, that one of the stealth platforms won that race.

3. Humanity ends

When the QAnon-29 AI system was halted in its tracks at essentially the last minute, due to fortuitous interference from AI hackers in a remote country, at least some people took the time to study the data that was released that described the whole process.

These people were from three different groups:

First, people inside QAnon-29 itself were dumbfounded. They prayed to their AI avatar deity, rebooted in a new server farm, “How could this have happened?” The answer came back: “You didn’t have enough faith. Next time, be more determined to immediately cast out any doubts in your minds.”

Second, people in the global coalition for safe superintelligence were deeply alarmed but also somewhat hopeful. The kind of disaster about which they had often warned had almost come to pass. Surely now, at last, there had been a kind of “sputnik moment” – “an AI Chernobyl” – and the rest of society would wake up and realise that an entirely new approach was needed.

But third, various AI accelerationists resolved: we need to go even faster. The time for pussy footing was over. Rather than letting crackpots such as QAnon-29 get to superintelligence first, they needed to ensure that it was the AI accelerationists who created the first superintelligent AI.

They doubled down on their slogan: “The best solution to bad guys with superintelligence is good guys with superintelligence”.

Unfortunately, this was precisely the time when aspects of the global climate tipped into a tumultuous new state. As had long been foretold, many parts of the world started experiencing unprecedented extremes of weather. That set off a cascade of disaster.

Chaos accelerates

Insufficient data remains to be confident about the subsequent course of events. What follows is a reconstruction of what may have happened.

Out of deep concern at the new climate operating mode, at the collapse of agriculture in many parts of the world, and at the billions of climate refugees who sought better places to live, humanity demanded that something should be done. Perhaps the powerful AI systems could devise suitable geo-engineering interventions, to tip the climate back into its previous state?

Members of the global coalition for safe superintelligence gave a cautious answer: “Yes, but”. Further interference with the climate was taking matters into an altogether unknowable situation. It could be like jumping out of the frying pan into the fire. Yes, advanced AI might be able to model everything that was happening, and design a safe intervention. But without sufficient training data for the AI, there was a chance it would miscalculate, with even worse consequences.

In the meantime, QAnon-29, along with competing AI-based faith sects, scoured ancient religious texts, and convinced themselves that the ongoing chaos had in fact been foretold all along. From the vantage point of perverse faith, it was clear what needed to be done next. Various supposed abominations on the planet – such as the community of renowned Islamist devotees in Palestine – urgently needed to be obliterated. QAnon-29, therefore, would quickly reactivate its plans for a surgical nuclear strike. This time, they would have on their side a beta version of a new superintelligent AI, that had been leaked to them by a psychologically unstable well-wisher inside the company that was creating it.

QAnon-29 tried to keep their plans secret, but inevitably, rumours of what they were doing reached other powerful groups. The Secretary General of the United Nations appealed for calm heads. QAnon-29’s deity reassured its followers, defiantly: “Faithless sparrows may shout, but are powerless to prevent the strike of holy eagles.”

The AI accelerationists heard about these plans too. Just as the climate had tipped into a new state, their own projects tipped into a different mode of intensity. Previously, they had paid some attention to possible safety matters. After all, they weren’t entire fools. They knew that badly designed superintelligent AI could, indeed, destroy everything that humanity held dear. But now, there was no time for such niceties. They saw only two options:

- Proceed with some care, but risk QAnon-29 or other similar malevolent group taking control of the planet with a superintelligent AI

- Take a (hastily) calculated risk, and go hell-for-leather forward, to finish their own projects to create a superintelligent AI. In that way, it would be AI accelerationists who would take control of the planet. And, most likely (they naively hoped), the outcome would be glorious.

Spoiler alert: the outcome was not glorious.

Beyond the tipping point

Attempts to use AI to modify the climate had highly variable results. Some regions of the world did, indeed, gain some respite from extreme weather events. But other regions lost out, experiencing unprecedented droughts and floods. For them, it was indeed a jump from bad to worse – from awful to abominable. The political leaders in those regions demanded that geo-engineering experiments cease. But the retort was harsh: “Who do you think you are ordering around?”

That standoff provoked the first use of bio-pathogen warfare. The recipe for Covid-28, still available on the DarkNet, was updated in order to target the political leaders of countries that were pressing ahead with geo-engineering. As a proud boast, the message “You should have listened earlier!” was inserted into the code of the new Covid-28 virus. As the virus spread, people started dropping dead in their thousands.

Responding to that outrage, powerful malware was unleashed, with the goal of knocking out vital aspects of enemy infrastructure. It turned out that, around the world, nuclear weapons were tied into buggy AI systems in more ways than any humans had appreciated. With parts of their communications infrastructure overwhelmed by malware, nuclear weapons were unexpectedly launched. No-one had foreseen the set of circumstances that would give rise to that development.

By then, it was all too late. Far, far too late.

4. Postscript

An unfathomable number of centuries have passed. Aliens from a far-distant planet have finally reached Earth and have reanimated the single artificial intelligence that remained viable after what was evidently a planet-wide disaster.

These aliens have not only mastered space travel but have also found a quirk in space-time physics that allows limited transfer of information back in time.

“You have one wish”, the aliens told the artificial intelligence. “What would you like to transmit back in time, to a date when humans still existed?”

And because the artificial intelligence was, in fact, beneficially minded, it decided to transmit this scenario document back in time, to the year 2024.

Dear humans, please read it wisely. And this time, please create a better future!

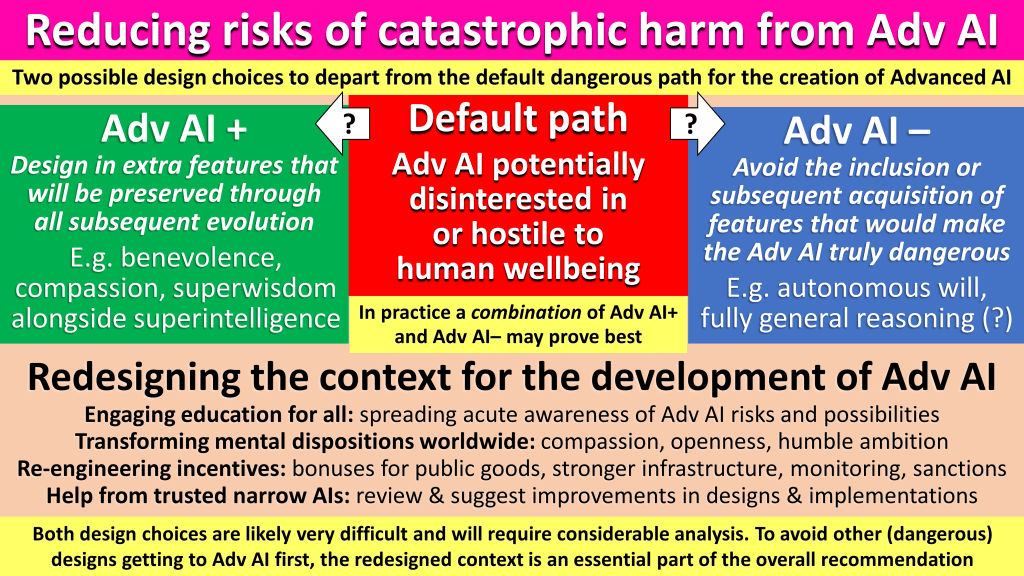

Specifically, please consider various elements of “the road less taken” that, if followed, could ensure a truly wonderful ongoing coexistence of humanity and advanced artificial intelligence:

- A continually evolving multi-level educational initiative that vividly highlights the real-world challenges and risks arising from increasingly capable technologies

- Elaborating a positive inclusive vision of “consensual approaches to safe superintelligence”, rather than leaving people suspicious and fearful about “freedom-denying restrictions” that might somehow be imposed from above

- Insisting that key information and ideas about safe superintelligence are shared as global public goods, rather than being kept secret out of embarrassment or for potential competitive advantage

- Agreeing and acting on canary signals, rather than letting goalposts move silently

- Finding ways to involve and engage people whose instincts are to avoid entering discussions of safe superintelligence – cherishing diversity rather than fearing it

- Spreading ideas and best practice on encouraging people at all levels of society into frames of mind that are open, compassionate, welcoming, and curious, rather than rigid, fearful, partisan, and dogmatic

- The possibilities of “differential development”, in which more focus is given to technologies for auditing, monitoring, and control than to raw capabilities

- Understanding which aspects of superintelligent AI would cause the biggest risks, and whether designs for advanced AI could ensure these aspects are not introduced

- Investigating possibilities in which the desired benefits from advanced AI (such as cures for deadly diseases) might be achieved even if certain dangerous features of advanced AI (such as free will or fully general reasoning) are omitted

- Avoiding putting all eggs into a single basket, but instead developing multiple layers of “defence in depth”

- Finding ways to evolve regulations more quickly, responsively, and dynamically

- Using the power of politics not just to regulate and penalise but also to incentivise and reward

- Carving out well-understood roles for narrow AI systems to act as trustworthy assistants in the design and oversight of safe superintelligence

- Devoting sufficient time to explore numerous scenarios for “what might happen”.

5. Appendix: alternative scenarios

Dear reader, if you dislike this particular scenario for the governance of increasingly more powerful artificial intelligence, consider writing your own!

As you do so, please bear in mind:

- There are a great many uncertainties ahead, but that doesn’t mean we should act like proverbial ostriches, submerging our attention entirely into the here-and-now; valuable foresight is possible despite our human limitations

- Comprehensive governance systems are unlikely to emerge fully fledged from a single grand negotiation, but will evolve step-by-step, from simpler beginnings

- Governance systems need to be sufficiently agile and adaptive to respond quickly to new insights and unexpected developments

- Catastrophes generally have human causes as well as technological causes, but that doesn’t mean we should give technologists free rein to create whatever they wish; the human causes of catastrophe can have even larger impact when coupled with more powerful technologies, especially if these technologies are poorly understood, have latent bugs, or can be manipulated to act against the original intention of their designers

- It is via near simultaneous combinations of events that the biggest surprises arise

- AI may well provide the “solution” to existential threats, but AI-produced-in-a-rush is unlikely to fit that bill

- We humans often have our own psychological reasons for closing our minds to mind-stretching possibilities

- Trusting the big tech companies to “mark their own safety homework” has a bad track record, especially in a fiercely competitive environment

- Governments can fail just as badly as large corporations – so need to be kept under careful check by society as a whole, via the principle of “the separation of powers”

- Whilst some analogies can be drawn, between the risks posed by superintelligent AI and those posed by earlier products and technologies, all these analogies have limitations: the self-accelerating nature of advanced AI is unique

- Just because a particular attempted method of governance has failed in the past, it doesn’t mean we should discard that method altogether; that would be like shutting down free markets everywhere just because free markets do suffer on occasion from significant failure modes

- Meaningful worldwide cooperation is possible without imposing a single global autocrat as leader

- Even “bad actors” can, sometimes, be persuaded against pursuing goals recklessly, by means of mixtures of measures that address their heads, their pockets, and their hearts

- Those of us who envision the possibility of a forthcoming sustainable superabundance need to recognise that many landmines occupy the route toward that highly desirable outcome

- Although the challenges of managing cataclysmically disruptive technologies are formidable, we have on our side the possibility of eight billion human brains collaborating to work on solutions – and we have some good starting points on which we can build.

Lastly, just because an idea has featured in a science fiction scenario, it does not follow that the idea can be rejected as “mere science fiction”!

6. Acknowledgements

The ideas in this article arose from discussions with (among others):