Six possible responses as the Economic Singularity approaches. Which do you pick?

Over the course of the next few decades, work and income might be fundamentally changed. A trend that has been seen throughout human history might be raised to a pivotal new level:

- New technologies – primarily the technologies of intelligent automation – will significantly reduce the scope for human involvement in many existing work tasks;

- Whilst these same technologies will, in addition, lead to the creation of new types of work tasks, these new tasks, like the old ones, will generally also be done better by intelligent automation than via human involvement;

- That is, the new jobs (such as “robot repair engineer” or “virtual reality experience designer”) will be done better, for the most part, by advanced robots than by humans;

- As a result, more and more people will be unable to find work that pays them what they consider to be a sufficient income.

Indeed, technological changes result, not only in new products, but in new ways of living. The faster and more extensive the technological changes, the larger the scope for changes in lifestyle, including changes in how we keep healthy, how we learn things, how we travel, how we house ourselves, how we communicate and socialise, how we entertain ourselves, and – of particular interest for this essay – how we work and how we are paid.

But here’s the dilemma in this scenario. Although automation will be capable of producing everything that people require for a life filled with flourishing, most people will be unable to pay for these goods and services. Lacking sufficient income, the majority of people will lose access to good quality versions of some or all of the following: healthcare, education, travel, accommodation, communications, and entertainment. In short, whilst a small group of people will benefit handsomely from the products of automation, the majority will be left behind.

This dilemma cannot be resolved merely by urging the left behinds to “try harder”, to “learn new skills”, or (in the words attributed to a 1980s UK politician) to “get on a bike and travel to where work is available”. Such advice was relevant in previous generations, but it will no longer be sufficient. No matter how hard they try, the majority of people won’t be able to compete with tireless, relentless smart machinery powered by new types of artificial intelligence. These robots, avatars, and other automated systems will demonstrate not only diligence and dexterity but also creativity, compassion, and even common sense, making them the preferred choice for most tasks. Humans won’t be able to compete.

This outcome is sometimes called “The Economic Singularity” – a term coined by author and futurist Calum Chace. It will involve a singular transition in humanity’s mode of economics:

- From when most people expect to be able to earn money by undertaking paid work for a significant part of their life

- To when most people will be unable to earn sufficient income from paid work.

So what are our options?

Here are six to consider, each of which have advocates rooting for them:

- Disbelieve in the possibility of any such large-scale job losses within the foreseeable future

- Accept the rise of new intelligent automation technologies, but take steps to place ourselves in the small subset of society that particularly benefits from them

- Resist the rise of these new technologies. Prevent these systems from being developed or deployed at scale

- Steer the rise of these new technologies, so that plenty of meaningful, high-value roles remain for humans in the workforce

- Simplify our lifestyles, making do with less, so that most of us can have a pleasant life even without access to the best outputs of intelligent automation technologies

- Enhance, with technology, not just the mechanisms to create products but also the mechanisms used in society for the sharing of the benefits of products.

In this essay, I’ll explore the merits and drawbacks of these six options. My remarks split into three sections:

- Significant problems with each of the first five options listed

- More details of the sixth option – “enhance” – which is the option I personally favour

- A summary of what I see as the vital questions arising – questions that I invite other writers to address.

A: Significant challenges ahead

A1: “Disbelieve”

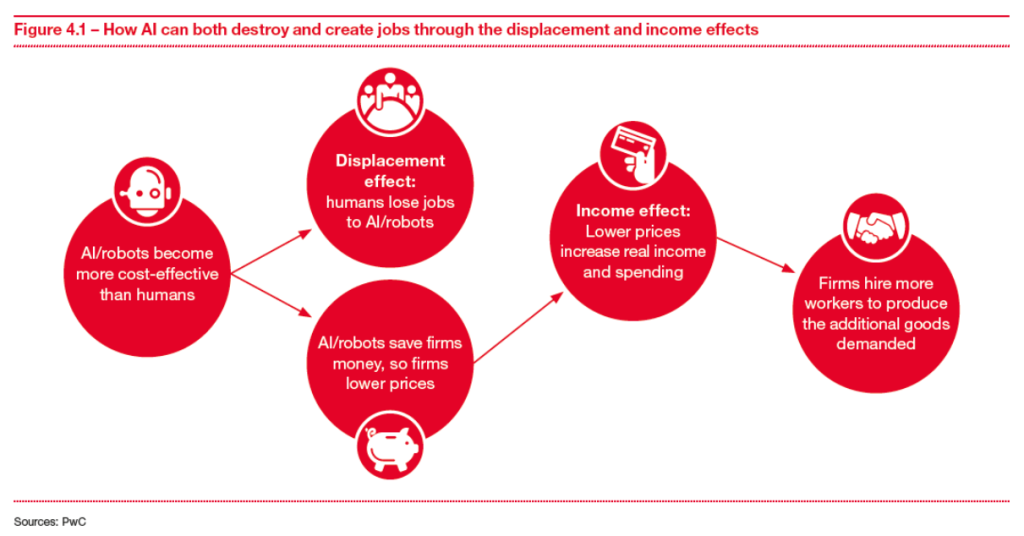

At first glance, there’s a lot in favour of the “disbelieve” option. The evidence from human history, so far, is that technology has had three different impacts on the human workforce, with the net impact always being positive:

- A displacement factor, in which automation becomes able to do some of the work tasks previously performed by humans

- An augmentation factor, in which humans become more capable when they take advantage of various tools provided by technology, and are able to do some types of work task better than before – types of work that take on a new significance

- An expansion factor, in which the improvements to productivity enabled by the two previous factors generate economic growth, leading to consumers wanting more goods and services than before. This in turn provides more opportunities for people to gain employment helping to provide these additional goods and services.

For example, some parts of the work of a doctor may soon be handled by systems that automatically review medical data, such as ultrasound scans, blood tests, and tissue biopsies. These systems will be better than human doctors in detecting anomalies, in distinguishing between false alarms and matters of genuine concern, and in recommending courses of treatment that take fully into account the unique personal circumstances of each patient. That’s the displacement effect. In principle, that might leave doctors more time to concentrate on the “soft skills” parts of their jobs: building rapport with patients, gently coaxing them to candidly divulge all factors relevant to their health, and inspiring them to follow through on courses of treatment that may, for a while, have adverse side effects. The result in this narrative: patients receive much better healthcare overall, and are therefore especially grateful to their doctors. Human doctors will remain much in demand!

More generally, automation systems might cover the routine parts of existing work, but leave in human hands the non-routine aspects – the parts which cannot be described by any “algorithm”.

However, there are three problems with this “disbelieve” narrative.

First, automation is increasingly able to cover supposedly “non-routine” tasks as well as routine tasks. Robotic systems are able to display subtle signs of emotion, to talk in a reassuring tone of voice, to suggest creative new approaches, and, more generally, to outperform humans in soft skills (such as apparent emotional intelligence) as well as in hard skills (such as rational intelligence). These systems gain their abilities, not by any routine programming with explicit instructions, but by observing human practices and learning from them, using methods known as “machine learning”. Learning via vast numbers of repeated trials in simulated virtual environments adds yet more capabilities to these systems.

Second, it may indeed be the case that some tasks will remain to be done by humans. It may be more economically effective that way: consider the low-paid groups of human workers who manually wash people’s cars, sidelining fancy machines that can also do that task. It may also be a matter of human preference: we might decide we occasionally prefer to buy handmade goods rather than ones that have been expertly produced by machines. However, there is no guarantee that there will be large numbers of these work roles. Worse, there is no guarantee that these jobs will be well-paid. Consider again the poorly paid human workers who wash cars. Consider also the lower incomes received by Uber drivers than, in previous times, by drivers of old-fashioned taxis where passengers paid a premium for the specialist navigational knowledge acquired by the drivers over many years of training.

Third, it may indeed be the case that companies that operate intelligent automation technologies receive greater revenues as a result of the savings they make in replacing expensive human workers with machinery with a lower operating cost. But there is no guarantee that this increased income, and the resulting economic expansion, will result in more jobs for humans. Instead, the extra income may be invested in yet more technology, rather than in hiring human workers.

In other words, there is no inevitability about the ongoing relevance of the augmentation and expansion factors.

What’s more, this can already be seen in the statistics of rising inequality within society:

- A growing share of income in the hands of the top 0.1% of salaries

- A growing share of income from investments instead of from salaries

- A growing share of wealth in the hands of the top 0.1% wealth owners

- Declining median incomes at the same time as mean incomes rise.

This growing inequality is due at least in part to the development and adoption of more powerful automation technologies:

- Companies can operate with fewer human staff, and gain their market success due to the technologies they utilise

- Online communications and comparison tools mean that lower-quality output loses its market presence more quickly to output with higher quality; this is the phenomenon of “winner takes all” (or “winner takes most”)

- Since the contribution of human workers is less critical, any set of workers who try to demand higher wages can more easily be replaced by other workers (perhaps overseas) who are willing to accept lower wages (consider again the example of teams of car washers).

In other words, we may already be experiencing an early wave of the Economic Singularity, arriving before the full impact takes place:

- Intelligent automation technologies are already giving rise to a larger collection of people who consider themselves to be “left behind”, unable to earn as much money as they previously expected

- Oncoming, larger waves will rapidly increase the number of left behinds.

Any responses we have in mind for the Economic Singularity should, therefore, be applied now, to address the existing set of left behinds. That’s instead of society waiting until many more people find themselves, perhaps rather suddenly, in that situation. By that time, social turmoil may make it considerably harder to put in place a new social contract.

To be clear, there’s no inevitability about how quickly the full impact of the Economic Singularity will be felt. It’s even possible that, for unforeseen reasons, such an impact might never arise. However, society needs to think ahead, not just about inevitabilities, but also about possibilities – and especially about possibilities that seem pretty likely.

That’s the case for not being content with the “disbelieve” option. It’s similar to the case for rejecting any claims that:

- Many previous predictions of global pandemics turned out to be overblown; therefore we don’t need to make any preparations for any future breakthrough global pandemic

- Previous predictions of nuclear war between superpowers turned out not to be fulfilled; therefore we can stop worrying about future disputes escalating into nuclear exchanges.

No: that ostrich-like negligence, looking away from risks of social turmoil in the run-up to a potential Economic Singularity, would be grossly irresponsible.

A2: “Accept”

As a reminder, the “accept” option is when some people accept that there will be large workplace disruption due to the rise of new intelligent automation technologies, with the loss of most jobs, but when these people are resolved to take steps to place themselves in the small subset of society that particularly benefits from these disruptions.

Whilst it’s common to hear people argue, in effect, for the “disbelieve” viewpoint covered in the previous subsection, it’s much rarer for someone to openly say they are in favour of the “accept” option.

Any such announcement would tend to mark the speaker as being self-centred and egotistical. They evidently believe they are among a select group who have what it takes to succeed in circumstances where most people will fail.

Nevertheless, it’s a position that some people might see as “the best of a set of bad options”. They may think to themselves: Waves of turbulence are coming. It’s not possible to save everyone. Indeed, it’s only possible to save a small subset of the population. The majority will be left behind. In that context, they urge themselves: Stop overthinking. Focus on what’s manageable: one’s own safety and security. Find one of the few available lifeboats and jump in quickly. Don’t let yourself worry about the fates of people who are doomed to a less fortunate future.

This position may strike someone as credible to the extent that they already see themselves as one of society’s winners:

- They’ve already been successful in business

- They assess themselves as being healthy, smart, focused, and pragmatic

- They intend to keep on top of new technological possibilities: they’ll learn about the strengths and weaknesses of various technologies of intelligent automation, and exploit that knowledge.

What’s more, they may subscribe to a personal belief that “heroes make their own destiny”, or similar.

But before you adopt the “accept” stance, here are six risks you should consider:

- The skills in which you presently take pride, as supposedly being beyond duplication by any automated system, may unexpectedly be rendered obsolete due to technology progressing more quickly and more comprehensively than you expected. You might therefore find yourself, not as one of society’s winners, but as part of the growing “left behind” community

- Even if some of your skills remain unmatched by robots or AIs, these skills may have played less of a role than you thought in your past successes; some of these past successes may also have involved elements of good fortune, or personal connections, and so on. These auxiliary factors may give you a different outcome the next time you “roll the dice” and try to change from one business opportunity to another. Once again, you may find yourself unexpectedly in the social grouping left behind by technological change

- Even if you personally do well in the turmoil of increased job losses and economic transformation, what about all the people that matter a lot to you, such as family members and special friends? Is your personal success going to be sufficient that you can provide a helping hand to everyone to whom you feel a tie of closeness? Or are you prepared to stiffen your attitudes and to break connections with people from these circles of family and friends, as they become “left behind”?

- Many people who end up as left behinds will suffer physical, mental, or emotional pain, potentially including what are known as “deaths of despair”. Are you prepared to ignore all that suffering?

- Some of the left behinds may be inclined to commit crimes, to acquire some of the goods and services from which they are excluded by their state of relative poverty. That implies that security measures will have to be stepped up, including strict borders. You might be experiencing a life of material abundance, but with the drawback of living inside a surveillance-state society that is psychologically embittered

- Some of the left behinds might go one step further, obtaining dangerous weapons, leading to acts of mass terrorism. In case they manage to access truly destructive technologies, the result might be catastrophic harm or even existential destruction.

In deciding between different social structures, it can be helpful to adopt an approach proposed by the philosopher John Rawls, known as “the veil of ignorance”. In this approach, we are asked to set aside our prior assumptions about which role in society we will occupy. Instead, we are asked to imagine that we have an equal probability of obtaining any of the positions within that society.

For example, consider a society we’ll call WLB, meaning “with left behinds”, in which 995 people out of every one thousand are left behind, and five of every thousand have an extremely good standard of living (apart from having to deal with the problems numbered 4, 5, and 6 in the above list). Consider, as an alternative, a society we’ll call NLB, “no one left behind”, in which everyone has a quality of living that can be described as “good” (if, perhaps, not as “extremely good”).

If we don’t know whether we’ll be one of the fortunate 0.5% of the population, would we prefer society WLB or society NLB?

The answer might seem obvious: from behind the veil of ignorance, we should strongly prefer NLB. However, this line of argument is subject to two objections. First, someone might feel sure that they really will end up as part of the 0.5%. But that’s where the problems numbered 1 and 2 in the above list should cause a reconsideration.

The second objection deserves more attention. It is that a society such as NLB may be an impossibility. Attempts to create NLB might unintentionally lead to even worse outcomes. After all, bloody revolutions over recent centuries have often veered catastrophically out of control. Self-described “vanguards” of a supposedly emergent new society have turned into brutal demagogues. Attempts to improve society through the ballot box have frequently failed too – prompting the acerbic remark by former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher that (to paraphrase) “the problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people’s money”.

It is the subject of the remainder of this essay to assess whether NLB is actually practical. (If not, we might have to throw our efforts behind “Accept” after all.)

A3: “Resist”

The “resist” idea starts from a good observation. Just because something is possible, it doesn’t mean that society should make it happen. In philosophical language, a could does not imply a should.

Consider some examples. Armed forces in the Second World War could have deployed chemical weapons that emitted poison gas – as had happened during the First World War. But the various combatants decided against that option. They decided: these weapons should not be used. In Victorian times, factory owners could have employed young children to operate dangerous machinery with their nimble fingers, but society decided, after some deliberation, that such employment should not occur. Instead, children should attend school. More recently, nuclear power plants could have been constructed with scant regard to safety, but, again, society decided that should not happen, and that safety was indeed vital in these designs.

Therefore, just because new technologies could be developed and deployed to produce various goods and services for less cost than human workers, there’s no automatic conclusion in favour of that happening. Just as factory owners were forbidden from employing young children, they could also be forbidden from employing robots. Societal attitudes matter.

In this line of thinking, if replacing humans with robots in the workplace will have longer term adverse effects, society ought to be able to decide against that replacement.

But let’s look more closely at the considerations in these two cases: banning children from factories, and banning robots from factories. There are some important differences:

- The economic benefits to factory owners from employing children were significant but were declining: newer machinery could operate without requiring small fingers to interact with them

- The economy as a whole needed more workers who were well educated; therefore it made good economic sense for children to attend school rather than work in factories

- The economic benefits to factory owners from deploying robots are significant and are increasing: newer robots can work at even higher levels of efficiency and quality, and cost less to operate

- The economy as a whole has less need of human workers, so there is no economic argument in favour of prioritising the employment and training of human workers instead of the deployment of intelligent automation.

Moreover, it’s not just “factory owners” who benefit from being able to supply goods and services at lower cost and higher quality. Consumers of these goods and services benefit too. Consider again the examples of healthcare, education, travel, accommodation, communications, and entertainment. Imagine choices between:

- High-cost, low-quality healthcare, provided mainly by humans, versus low-cost, high-quality healthcare, provided in large part by intelligent automation

- High-cost, low-quality education, provided mainly by humans, versus low-cost, high-quality education, provided in large part by intelligent automation

- And so on.

The “resist” option therefore would imply acceptance of at least part of the “simplify” option (discussed in more depth later): people in that circumstance would need to accept lower quality provision of healthcare, education, travel, accommodation, communications, and entertainment.

In other words, the resist option implies saying “no” to many possible elements of technological progress and the humanitarian benefits arising from it.

In contrast, the “steer” option tries to say “yes” to most of the beneficial elements of technological progress, whilst still preserving sufficient roles for humans in workforces. Let’s look more closely at it.

A4: “Steer”

The “steer” option tries to make a distinction between:

- Work tasks that are mainly unpleasant or tedious, and which ought to be done by intelligent automation rather than by humans

- Work tasks that can be meaningful or inspiring, especially when the humans carrying out these tasks have their abilities augmented (but not superseded) by intelligent automation (this concept was briefly mentioned in discussion of the “Disbelieve” option).

The idea of “steer” is to prioritise the development and adoption of intelligent automation technologies that can replace human workers in the first, tedious, category of tasks, whilst augmenting humans so they can continue to carry out the second, inspiring, category of tasks.

This also means a selective resistance to improvements in automation technologies, namely to those improvements which would result in the displacement of humans from the second category of tasks.

This proposal has been championed by, for example, the Stanford economist Erik Brynjolfsson. Brynjolfsson has coined the phrase “the Turing Trap”, referring to what he sees as a mistaken direction in the development of AI, namely trying to create AIs that can duplicate (and then exceed) human capabilities. Such AIs would be able to pass the “Turing Test” that Alan Turing famously described in 1950, but that would lead, in Brynjolfsson’s view, to a fearsome “peril”:

Building machines designed to pass the Turing Test and other, more sophisticated metrics of human-like intelligence… is a path to unprecedented wealth, increased leisure, robust intelligence, and even a better understanding of ourselves. On the other hand, if [that] leads machines to automate rather than augment human labor, it creates the risk of concentrating wealth and power. And with that concentration comes the peril of being trapped in an equilibrium where those without power have no way to improve their outcomes.

Here’s how Brynjolfsson introduces his ideas:

Creating intelligence that matches human intelligence has implicitly or explicitly been the goal of thousands of researchers, engineers, and entrepreneurs. The benefits of human-like artificial intelligence (HLAI) include soaring productivity, increased leisure, and perhaps most profoundly, a better understanding of our own minds.

But not all types of AI are human-like – in fact, many of the most powerful systems are very different from humans – and an excessive focus on developing and deploying HLAI can lead us into a trap. As machines become better substitutes for human labor, workers lose economic and political bargaining power and become increasingly dependent on those who control the technology. In contrast, when AI is focused on augmenting humans rather than mimicking them, then humans retain the power to insist on a share of the value created. What’s more, augmentation creates new capabilities and new products and services, ultimately generating far more value than merely human-like AI. While both types of AI can be enormously beneficial, there are currently excess incentives for automation rather than augmentation among technologists, business executives, and policymakers.

Accordingly, here are his recommendations:

The future is not preordained. We control the extent to which AI either expands human opportunity through augmentation or replaces humans through automation. We can work on challenges that are easy for machines and hard for humans, rather than hard for machines and easy for humans. The first option offers the opportunity of growing and sharing the economic pie by augmenting the workforce with tools and platforms. The second option risks dividing the economic pie among an ever-smaller number of people by creating automation that displaces ever-more types of workers.

While both approaches can and do contribute to progress, too many technologists, businesspeople, and policymakers have been putting a finger on the scales in favor of replacement. Moreover, the tendency of a greater concentration of technological and economic power to beget a greater concentration of political power risks trapping a powerless majority into an unhappy equilibrium: the Turing Trap….

The solution is not to slow down technology, but rather to eliminate or reverse the excess incentives for automation over augmentation. In concert, we must build political and economic institutions that are robust in the face of the growing power of AI. We can reverse the growing tech backlash by creating the kind of prosperous society that inspires discovery, boosts living standards, and offers political inclusion for everyone. By redirecting our efforts, we can avoid the Turing Trap and create prosperity for the many, not just the few.

But a similar set of questions arise for the “steer” option as for the more straightforward “resist” option. Resisting some technological improvements, in order to preserve employment opportunities for humans, means accepting a lower quality and higher cost of the corresponding goods and services.

Moreover, that resistance would need to be coordinated worldwide. If you resist some technological innovations but your competitors accept them, and replace expensive human workers with lower cost AI, their products can be priced lower in the market. That would drive you out of business – unless your community is willing to stick with the products that you produce, relinquishing the chance to purchase cheaper products from your competitors.

Therefore, let’s now consider what would be involved in such a relinquishment.

A5: “Simplify”

If some people prefer to adopt a simpler life, without some of the technological wonders that the rest of us expect, that choice should be available to them.

Indeed, human society has long upheld the possibility of choice. Communities are able, if they wish, to make their own rules about the adoption of various technologies.

For example, organisers of various sports set down rules about which technological enhancements are permitted, within those sports, and which are forbidden. Bats, balls, protective equipment, sensory augmentation – all of these can be restricted to specific dimensions and capabilities. The restrictions are thought to make the sports better.

Similarly, goods sold in various markets can carry markings that designate them as being manufactured without the use of certain methods. Thus consumers can see an “organic” label and be confident that certain pesticides and fertilisers have been excluded from the farming methods used to produce these foods. Depending on the type of marking, there can also be warranties that these foods contain no synthetic food additives and have not been processed using irradiation or industrial solvents.

Consider also the Amish, a group of traditionalist communities from the Anabaptist tradition, with their origins in Swiss German and Alsatian (French) cultures. These communities have made many decisions over the decades to avoid aspects of the technology present in wider society. Their clothing has avoided buttons, zips, or Velcro. They generally own no motor cars, but use horse-drawn carts for local transport. Different Amish communities have at various times forbidden (or continue to forbid) high-voltage electricity, powered lawnmowers, mechanical milking machines, indoor flushing toilets, bathtubs with running water, refrigerators, telephones inside the house, radios, and televisions.

Accordingly, whilst some parts of human society might in the future adopt fuller use of intelligent automation technologies, deeply transforming working conditions, other parts might, Amish-like, decide to abstain. They may say: “we already have enough, thank you”. Whilst people in society as a whole may be unable to find work that pays them good wages, people in these “simplified” communities will be able to look after each other.

Just as Amish communities differ among themselves as to how much external technology they are willing to incorporate into their lives, different “simplified” communities could likewise make different choices as to how much they adopt technologies developed outside their communities. Some might seek to become entirely self-sufficient; others might wish to take advantage of various medical treatments, educational software, transportation systems, robust housing materials, communications channels, and entertainment facilities provided by the technological marvels created in wider society.

But how will these communities pay for these external goods and services? In order to be able to trade, what will they be able to create that is not already available in better forms outside their communities, where greater use is made of intelligent automation?

We might consider tourist visits, organic produce, or the equivalent of handmade ornaments. But, again, what will make these goods more attractive, to outsiders, than the abundance of goods and services (including immersive virtual reality travel) that is already available to them?

We therefore reach a conclusion: groups that choose to live apart from deeply transformative technologies will likely lack access to many valuable goods and services. It’s possible they may convince themselves, for a while, that they prefer such a lifestyle. However, just as the attitudes of Amish communities have morphed over the decades, so that these groups now see (for example) indoor flushing toilets as a key part of their lives, it is likely that the attitudes of people in these simplified communities will also alter. When facing death from illness, or when facing disruption to their relatively flimsy shelters from powerful weather, they may well find themselves deciding they prefer, after all, to access more of the fruits of technological abundance.

With nothing to exchange or barter for these fruits, the only way they will receive them is via a change in the operation of the overall economy. That brings us to the sixth and final option from my original list, “enhance”.

Whereas the previous options have looked at various alterations in how technology is developed or applied, “enhance” looks at a different possibility: revising how the outputs and benefits of technology are planned and distributed throughout society. These are revisions to the economy, rather than revisions in technology.

In this vision, with changes in both technology and the economy, everyone will benefit handsomely. Simplicity will remain a choice, for those who prefer it, but it won’t be an enforced choice. People who wish to participate in a life of abundance will be able to make that choice instead, without needing to find especially remunerative employment to pay for it.

I’ll accept, in advance, that many critics may view such a possibility as a utopian fantasy. But let’s not rush to a conclusion. I’ll build my case in stages.

B: Enhancing the operation of the economy

Let’s pick up the conversation with the basics of economics, which is the study of how to deal with scarcity. When important goods and services are scarce, humans can suffer.

Two fundamental economic forces that have enabled astonishing improvements in human wellbeing over the centuries, overcoming many aspects of scarcity, are collaboration and competition:

- Collaboration: person A benefits from the skills and services of person B, whereas person B benefits reciprocally from a different set of skills and services of person A; this allows both A and B to specialise, in different areas

- Competition: person C finds a way to improve the skills and services that they offer to the market, compared to person D, and therefore receives a higher reward – causing person D to consider how to improve their skills and services in turn, perhaps by copying some of the methods and approach of person C.

What I’ve just described in terms of simple interactions between two people is nowadays played out, in practice, via much larger communities, and over longer time periods:

- Collaboration includes the provision of a social safety net, for looking after individuals who are less capable, older, lack resources, or who have fallen on hard times; these safety nets can operate at the family level, tribe (extended family) level, community level, national level, or international level

- The prospect of gaining extra benefits from better skills and services leads people to make personal investments, in training and tools, so that they can possess (for a while at least) an advantage in at least one market niche.

Importantly, it needs to be understood that various forms of collaboration and competition can have negative consequences as well as positive ones:

- A society that keeps extending an unconditional helping hand to someone who avoids taking personal responsibility, or to a group that is persistently dysfunctional, might end up diverting scarce resources from key social projects to being squandered by people for no good purpose

- In a race to become more economically dominant, other factors may be overlooked, such as social harmony, environmental wellbeing, and other so-called externalities.

In other words, the forces that can lead to social progress can also lead to social harm.

In loose terms, the two sets of negative consequences can be called “failure modes of socialism” and “failure modes of capitalism” – to refer to two historically significant terms in theories of economics, namely “socialism” and “capitalism”. These two broad frameworks are covered in the subsections ahead, along with key failure modes in each case. After that, we’ll consider models that aspire to transcend both sets of failure by delivering “the best of both worlds”.

To look ahead, it is the “best of both worlds” model that has the potential to be the best solution to the Economic Singularity.

B1: Need versus greed?

When there is a shortage of some product or service, how should it be distributed? To the richest, the strongest, the people who shout the loudest, the special friends of the producers, or to whom?

One answer to that question is given in the famous slogan, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”. In other words, each person should receive whatever they truly need, be it food, clothing, healthcare, accommodation, transportation, and so on.

That slogan was popularised by Karl Marx in an article he wrote in 1875, but earlier political philosophers had used it in the 1840s. Indeed, an antecedent can be found in the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament, referring to the sharing of possessions within one of the earliest groups of Christian believers:

All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of their possessions was their own, but they shared everything they had… There were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned land or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone who had need.

Significantly, Marx foresaw that principle of full redistribution as being possible only after technology (“the productive forces”) had sufficiently “increased”. It was partly for that reason that Joseph Stalin, despite being an avowed follower of Marx, wrote a different principle into the 1936 constitution of the Soviet Union: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his work”. Stalin’s justification was that the economy had not yet reached the required level of production, and that serious human effort was first required to reach peak industrialization.

This highlights one issue with the slogan, and with visions of society that seek to place that slogan at the centre of their economy: before products and services can be widely distributed, they need to be created. A preoccupation with distribution will fail unless it is accompanied by sufficient attention to creation. Rather than fighting over how a pie is divided, it’s important to make the pie larger. Then there will be much more to share.

A second issue is in the question of what counts as a need. Clothing is a need, but what about the latest fashion? Food is a need, but what about the rarest of fruits and vegetables? And what about “comfort food”: is that a need? Healthcare is a need, but what about a heart transplant? Transportation is a need, but what about intercontinental aeroplane flights?

A third issue with the slogan is that a resource that is assigned to someone’s perceived need is, potentially, a resource denied from a more productive use to which another person might put that resource. Money spent to provide someone with what they claim they need might have been invested elsewhere to create more resources, allowing more people to have what they claim that they need.

Thus the oft-admired saying attributed to Mahatma Gandhi, “The world has enough for everyone’s needs, but not everyone’s greed”, turns out to be problematic in practice. Who is to say what is ‘need’ and what is ‘greed’? Are desires for luxury goods always to be denigrated as ‘greed’? Isn’t life about enjoyment, vitality, and progress, rather than just calmly sitting down in a state of relative poverty?

B2: Socialism and its failures

There are two general approaches to handling the problems just described: centralised planning, and free-market allocation.

With centralised planning, a group of reputedly wise people:

- Keep on top of information about what the economy can produce

- Keep on top of information about what people are believed to actually need

- Direct the economy so that it makes a better job of producing what it has been decided that people need.

Therefore a central planner may dictate that more shoes of a certain type need to be produced. Or that drinks should be manufactured with less sugar in them, that particular types of power stations should be built, or that particular new drugs should be created.

That’s one definition of socialism: representatives of the public direct the economy, including the all-important “means of production” (factories, raw materials, infrastructure, and so on), so that the assumed needs of all members of society are met.

However, when applied widely within an economy, centralised planning approaches have often failed abysmally. Assumptions about what people needed often proved wrong, or out-of-date. Indeed, members of the public often changed their minds about what products were most important for them, especially after new products came into use, and their upsides and downsides could be more fully appreciated. Moreover, manufacturing innovations, such as new drugs, or new designs for power stations, could not be achieved simply by wishing them or “planning” them. Finally, people working in production roles often felt alienated, lacking incentives to apply their best ideas and efforts.

That’s where the alternative coordination mechanism – involving free markets – often fared better (despite problems of its own, which we’ll review in due course). The result of free markets has been significant improvements in the utility, attractiveness, performance, reliability, and affordability of numerous types of goods and services. As an example, modern supermarkets are one of the marvels of the world, being stocked from floor to ceiling with all kinds of items to improve the quality of daily life. People around the globe have access to a vast variety of all-around nourishment and experience that would have astonished their great-grandparents.

In recent decades, there have been similar rounds of sustained quality improvement and cost reduction for personal computers, smartphones, internet access, flatscreen TVs, toys, kitchen equipment, home and office furniture, clothing, motor cars, aeroplane tickets, solar panels, and much more. The companies that found ways to improve their goods and services flourished in the marketplace, compelling their competitors to find similar innovations – or go out of business.

It’s no accident that the term “free market” contains the adjective “free”. The elements of a free market which enable it to produce a stream of quality improvements and cost reductions include the following freedoms:

- The freedom for companies to pursue profits – under the recognition that the prospect of earning profits can incentivise sustained diligence and innovation

- The freedom for companies to adjust the prices for their products, and to decide by themselves the features contained in these products, rather than following the dictates of any centralised planner

- The freedom for groups of people to join together and start a new business

- The freedom for companies to enter new markets, rather than being restricted to existing product lines; new competitors keep established companies on their toes

- The freedom for employees to move to new roles in different companies, rather than being tied to their existing employers

- The freedom for companies to explore multiple ways to raise funding for their projects

- The freedom for potential customers to not buy products from established vendors, but to switch to alternatives, or even to stop using that kind of product altogether.

What’s more, the above freedoms are permissionless in a free market. No one needs to apply for a special licence from central authorities before one of these freedoms becomes available.

Any political steps that would curtail the above freedoms need careful consideration. The result of such restrictions could (and often do) include:

- A disengaged workforce, with little incentive to apply their inspiration and perspiration to the tasks assigned to them

- Poor responsiveness to changing market interest in various products and services

- Overproduction of products for which there is no market demand

- Companies having little interest in exploring counterintuitive combinations of product features, novel methods of assembly, new ways of training or managing employees, or other innovations.

Accordingly, anyone who wishes to see the distribution of high-quality products to the entire population needs to beware curtailing freedoms of entrepreneurs and innovators. That would be taking centralised planning too far.

That’s not to say that the economy should dispense with all constraints. That would raise its own set of deep problems – as we’ll review in the next subsection.

B3: Capitalism and its failures

Just as there are many definitions of socialism, there are many definitions of capitalism.

Above, I offered this definition of socialism: an economy in which production is directed by representatives of the public, with the goal that the assumed needs of all members of society are met. For capitalism, at least parts of the economy are directed, instead, by people seeking returns on the capital they invest. This involves lots of people making independent choices, of the types I have just covered: choices over prices, product features, types of product, areas of business to operate within, employment roles, manufacturing methods, partnership models, ways of raising investment, and so on.

But these choices depend on various rules being set and observed by society:

- Protection of property: goods and materials cannot simply be stolen, but require the payment of an agreed price

- Protection of intellectual property: various novel ideas cannot simply be copied, but require, for a specified time, the payment of an agreed licence fee

- Protection of brand reputation: companies cannot use misleading labelling or other trademarked imagery to falsely imply an association with another existing company with a good reputation

- Protection of contract terms: when companies or individuals enter into legal contracts, regarding employment conditions, supply timelines, fees for goods and services, etc., penalties for any breach of contract can be enforced

- Protection of public goods: shared items such as clean air, usable roads, and general safety mechanisms, need to be protected against decay.

These protections all require the existence and maintenance of a legal system in which justice is available to everyone – not just to the people who are already well-placed in society.

These are not the only preconditions for the healthy operation of free markets. The benefits of these markets also depend on the existence of viable competition, which prevents companies from resting on their laurels. However, seeking an easier life for themselves, companies may be tempted to organise themselves into cartels, with agreed pricing, or with products with built-in obsolescence. The extreme case of a cartel is a monopoly, in which all competitors have gone out of business, or have been acquired by the leading company in an industry. A monopoly lacks incentive to lower prices or to improve product quality. A related problem is “crony capitalism”, in which governments preferentially award business contracts to companies with personal links to government ministers. The successful operation of a free market depends, therefore, upon society’s collective vigilance to notice and break up cartels, to prevent the misuse of monopoly power, and to avoid crony capitalism.

Further, even when markets do work well, in ways that provide short-term benefits to both vendors and customers, the longer-term result can be profoundly negative. So-called “commons” resources can be driven into a state of ruin by overuse. Examples include communal grazing land, the water flowing in a river, fish populations, and herds of wild livestock. All individual users of such a resource have an incentive to take from it, either to consume it themselves, or to include it in a product to be sold to a third party. As the common stock declines, the incentive for each individual person to take more increases, so that they’re not excluded. But finally, the grassland is all bare, the river has dried up, the stocks of fish have been obliterated, or the passenger pigeon, great auk, monk seal, sea mink, etc., have been hunted to extinction. To guard against these perils of short-termism, various sorts of protective mechanisms need to be created, such as quotas or licences, with clear evidence of their enforcement.

What about when suppliers provide shoddy goods? In some cases, members of a society can learn which suppliers are unreliable, and therefore cease purchasing goods from them. In these cases, the market corrects itself: in order to continue in business, poor suppliers need to make amends. But when larger groups of people are involved, there are three drawbacks with just relying on this self-correcting mechanism:

- A vendor who deceives one purchaser in one vicinity can relocate to a different vicinity – or can simply become “lost in the crowd” – before deceiving another purchaser

- A vendor who produces poor-quality goods on a large scale can simultaneously impact lots of people’s wellbeing – as when a restaurant skimps on health and safety standards, and large numbers of diners suffer food poisoning as a result

- It may take a long time before defects in someone’s goods or services are discovered – for example, if no funds are available for an insurance payout that was contracted many years earlier.

It’s for such reasons that societies generally decide to augment the self-correction mechanisms of the free market with faster-acting preventive mechanisms, including requirements for people in various trades to conform to sets of agreed standards and regulations.

A final cause of market failure is perhaps the most significant: the way in which market exchanges fail to take “externalities” into account. A vendor and a purchaser may both benefit when a product is created, sold, and used, but other people who are not party to that transaction can suffer as a side effect – if, for example, the manufacturing process emits loud noises, foul smells, noxious gases, or damaging waste products. Since they are not directly involved in the transaction, these third parties cannot influence the outcome simply by ceasing to purchase the goods or services involved. Instead, different kinds of pressure need to be applied: legal restrictions, taxes, or other penalties or incentives.

It’s not just negative externalities that can cause free markets to misbehave. Consider also positive externalities, where an economic interaction has a positive impact on people who do not pay for it. Some examples:

- If a company purchases medical vaccinations for its employees, to reduce their likelihood of becoming ill with the flu, others in the community benefit too, since there will be fewer ill people in that neighbourhood, from whom they might catch flu

- If a company purchases on-the-job training for an employee, the employee may pass on to family members and acquaintances, free of charge, tips about some of the skills they learned

- If a company pays employees to carry out fundamental research, which is published openly, people in other companies can benefit from that research too, even though they did not pay for it.

The problem here is that the company may decide not to go ahead with such an investment, since they calculate that the benefits for them will not be sufficient to cover their costs. The fact that society as a whole would benefit, as a positive externality, generally does not enter their calculation.

This introduces the important concept of public goods. When there’s insufficient business case for an individual investor to supply the funding to cover the costs of a project, that project won’t get off the ground – unless there’s a collective decision for multiple investors to share in supporting it. Facilitating that kind of collective decision – one that would benefit society as a whole, rather than just a cartel of self-interested companies – takes us back to the notion of central planning. Central planners can consider longer-term possibilities – in ways that, as noted, are problematic for a free market to achieve – and can design and oversee what is known as industrial strategy or social strategy.

B4: The mixed market

To recap the last two subsections: there are problems with over-application of central planning, and there are also problems with free markets that have no central governance.

The conclusion to draw from this, however, isn’t to give up on both these ideas. It’s to seek an appropriate combination of these ideas. That combination is known as “the mixed market”. It involves huge numbers of decisions being taken locally, by elements of a free market, but all subject to democratic political oversight, aided by the prompt availability of information about the impacts of products in society and on the environment.

This division of responsibility between the free market and political oversight is described particularly well in the writing of political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson. They offer fulsome praise to something they say “may well be the greatest invention in history”. Namely, the mixed economy:

The combination of energetic markets and effective governance, deft fingers and strong thumbs.

Their reference to “deft fingers and strong thumbs” expands Adam Smith’s famous metaphor of the invisible hand which is said to guide the free market. Hacker and Pierson develop their idea as follows:

Governments, with their capacity to exercise authority, are like thumbs: powerful but lacking subtlety and flexibility. The invisible hand is all fingers. The visible hand is all thumbs. Of course, one wouldn’t want to be all thumbs. But one wouldn’t want to be all fingers, either. Thumbs provide countervailing power, constraint, and adjustment to get the best out of those nimble fingers…

The mixed economy… tackles a double bind. The private markets that foster prosperity so powerfully nonetheless fail routinely, sometimes spectacularly so. At the same time, the government policies that are needed to respond to these failures are perpetually under siege from the very market players who help to fuel growth. That is the double bind. Democracy and the market – thumbs and fingers – have to work together, but they also need to be partly independent from each other, or the thumb will cease to provide effective counterpressure to the fingers.

I share the admiration shown by Hacker and Pierson for the mixed market. I also agree that it’s hard to get the division of responsibilities right. Just as markets can fail, so also can politicians fail. But just as the fact of market failures should not be taken as a reason to dismantle free markets altogether, so should the fact of political failures not be taken as a reason to dismantle all political oversight of markets. Each of these two sorts of fundamentalist approaches – anti-market fundamentalism and pro-market fundamentalism – are dangerously one-sided. The wellbeing of society requires, not so much the reduction of government, but the rejuvenation of government, in which key aspects of government operation are improved:

- Smart, agile, responsive regulatory systems

- Selected constraints on the uses to which various emerging new technologies can be put

- “Trust-busting”: measures to prevent large businesses from misusing monopoly power

- Equitable redistribution of the benefits arising from various products and services, for the wellbeing and stability of society as a whole

- Identification, protection, and further development of public goods

- Industrial strategy: identifying directions to be pursued, and providing suitable incentives so that free market forces align toward these directions.

None of what I’m saying here should be controversial. However, both fundamentalist outlooks I mentioned often exert a disproportionate influence over political discourse. Part of the reason for this is explained at some length in the book by the researchers Hacker and Pierson which contained their praise for the mixed market. The title of that book is significant: American Amnesia: Business, Government, and the Forgotten Roots of Our Prosperity.

It’s not just that the merits of the mixed market have been “forgotten”. It’s that these merits have been deliberately obscured by a sustained ideological attack. That attack serves the interest of various potentially cancerous complexes that seek to limit governmental oversight of their activities:

- Big Tobacco, which tends to resist government oversight of the advertising of products containing tobacco

- Big Oil, which tends to resist government oversight of the emissions of greenhouse gases

- Big Armaments, which tends to resist government oversight of the growth of powerful weapons of mass destruction

- Big Finance, which tends to resist government oversight of “financial weapons of mass destruction” (to use a term coined by Warren Buffett)

- Big Agrotech, which tends to resist government oversight of new crops, new fertilisers, and new weedkillers

- Big Media, who tend to resist government oversight of press standards

- Big Theology, which resists government concerns about indoctrination and manipulation of children and others

- Big Money: individuals, families, and corporations with large wealth, who tend to resist the power of government to levy taxes on them.

All these groups stand to make short-term gains if they can persuade the voting public that the power of government needs to be reduced. It is therefore in the interest of these groups to portray the government as being inevitably systematically incompetent – and, at the same time, to portray the free market as being highly competent. But for the sake of society as a whole, these false portrayals must be resisted.

In summary: better governments can oversee economic frameworks in which better goods and services can be created (including all-important public goods):

- Frameworks involving a constructive combination of entrepreneurial flair, innovative exploration, and engaged workforces

- Frameworks that prevent the development of any large societal cancers that would divert too many resources to localised selfish purposes.

In turn, for the mixed model to work well, governments themselves must be constrained through oversight, by well-informed independent press, judiciary, academic researchers, and diverse political groupings, all supported by a civil service and challenged on a regular basis by free and fair democratic elections.

That’s the theory. Now for some complications – and solutions to the complications.

B5: Technology changes everything

Everything I’ve written in this section B so far makes sense independently of the oncoming arrival of the Economic Singularity. But the challenges posed by the Economic Singularity make it all the more important that we learn to temper the chaotic movements of the economy, with it operating responsively and thoughtfully under a high-calibre mixed market model.

Indeed, rapidly improving technology – especially artificial intelligence – is transforming the landscape, introducing new complications and new possibilities:

- Technology enables faster and more comprehensive monitoring of overall market conditions – including keeping track of fast-changing public expectations, as well as any surprise new externalities of economic transactions; it can thereby avoid some of the sluggishness and short-sightedness that bedevilled older (manual) systems of centralised planning and the oversight of entire economies

- Technology gives more information more quickly, not only to the people planning production (at either central or local levels), but also to consumers of products, with the result that vendors of better products will drive vendors of poorer products out of the market more quickly (this is the “winner takes all” phenomenon)

- With advanced technology playing an ever-increasing role in determining the success or failure of products, the companies that own and operate the most successful advanced technology platforms will become among the most powerful forces on the planet

- As discussed earlier (in Section A), technology will significantly reduce the opportunities for people to earn large salaries in return for work that they do

- Technology enables more goods to be produced at much lower cost – including cheaper clean energy, cheaper nutritious food, cheaper secure accommodation, and cheaper access to automated education systems.

Here, points 2, 3, and 4 raise challenges, leading to a world with greater inequalities:

- A small number of companies, and a small number of people working for them, will do very well in terms of income, and they will have unprecedented power

- The majority of companies, and the majority of people, will experience various aspects of failure and being “left behind”.

But points 1 and 5 promote a world where governance systems perform better, and where people need much less money in order to experience a high quality of wellbeing. They highlight the possibility of the mixed market model working better, distributing more goods and services to the entire population, and thereby meeting a wider set of needs. This comprehensive solution is what is meant by the word “enhance”, as in the name of my preferred solution to the Economic Singularity.

However, these improvements will depend on societies changing their minds about what matters most – the things that need to be closely measured, monitored, and managed. In short, it will depend on some fundamental changes in worldview.

B6: Measuring what matters most

The first key change in worldview is that the requirement for people to seek paid employment belongs only to a temporary phase in the evolution of human culture. That phase is coming to an end. From now on, the basis for societies to be judged as effective or defective shouldn’t be the proportion of people who have positions of well-paid employment. Instead, it should be the proportion of people who can flourish, every single day of their lives.

Moreover, measurements of prosperity must include adequate analysis of the externalities (both positive and negative) of economic transactions – externalities which market prices often ignore, but which modern AI systems can measure and monitor more accurately. These measurements will continue to include features such as wealth and average lifespan, as monitored by today’s politicians, but they’ll put a higher focus on broader measurements of wellbeing, therefore transforming where politicians will apply most of their attention.

In parallel, we should look forward to a stage-by-stage transformation of the social safety net – so that all members of society have access to the goods and services that are fundamental to experiencing an agreed base level of human flourishing, within a society that operates sustainably and an environment that remains healthy and vibrant.

I therefore propose the following high-level strategic direction for the economy: prioritise the reduction of prices for all goods and services that are fundamental to human flourishing, where the prices reflect all the direct and indirect costs of production.

This kind of price reduction is already taking place for a range of different products, such as many services delivered online, but there are too many other examples where prices are rising (or dropping too slowly).

In other words, the goal of the economy should no longer be to increase the GDP – the gross domestic product, made up of higher prices and greater commercial activity. Instead, the goal should be to reduce the true costs of everything that is required for a good life, including housing, food, education, security, and much more. This will be part of taking full advantage of the emerging tech-driven abundance.

It is when prices come down, that politicians should celebrate, not when prices go up, or when profit margins rise, or when the stock market soars.

The end target of this strategy is that all goods and services fundamental to human flourishing should, in effect, have zero price. But for the foreseeable future, many items will continue to have a cost.

For those goods and services which carry prices above zero, combinations of three sorts of public subsidies can be made available:

- An unconditional payment, sometimes called a UBI – an unconditional basic income – can be made available to all citizens of the country

- The UBI can be augmented by conditional payments, dependent on recipients fulfilling requirements agreed by society, such as, perhaps, education or community service

- There can be individual payments for people with special needs, such as particular healthcare requirements.

Such suggestions are not new, of course. Typically they face five main objections:

- A life without paid work will be one devoid of meaning – humans will atrophy as a result

- Giving people money for nothing will encourage idleness and decadence, and will be a poor use of limited resources

- A so-called “basic” income won’t be sufficient; what should be received by people who cannot (due to any fault of their own) earn a good salary, isn’t a basic income but a generous income (hence a UGI rather than a UBI) that supports a good quality of life rather than a basic existence

- The large redistribution of money to pay for a widespread UGI will cripple the rest of the economy, forcing taxpayers overseas; alternatively, if the UGI is funded by printing more money (as is sometimes proposed), this will have adverse inflationary implications

- Although a UBI might be affordable within a country that has an advanced developed economy, it will prove unaffordable in less developed countries, where the need for a UBI will be equally important; indeed, an inflationary spiral in countries that do pay their citizens a UBI will result in tougher balance-of-payments situations in the other countries of the world.

Let’s take these objections one at a time.

B7: Options for universal income

The suggestion that a life without paid work will have no possibility of deep meaning is, when you reflect on it, absurd, given the many profound experiences that people often have outside of the work context. The fact that this objection is raised so often is illuminating: it suggests a pessimism about one’s fellow human beings. People raising this objection usually say that they, personally, could have a good life without paid work; it’s just that “ordinary people” would be at a loss and go downhill, they suggest. After all, these critics may continue, look at how people often waste welfare payments they receive. Which takes us to the second objection on the list above.

However, the suggestion that unconditional welfare payments result in idleness and decadence has little evidence to support it. Many people who receive unconditional payments from the state – such as pension payments in their older age – live a fulfilling, active, socially beneficial life, so long as they remain in good health.

The criteria “remain in good health” is important here. People who abuse welfare payments often suffer from prior emotional malaise, such as depression, or addictive behaviours. Accordingly, the solution to welfare payments being (to an extent) wasted, isn’t to withdraw these payments, but is to address the underlying emotional malaise. This can involve:

- Making society healthier generally, via a fuller and wider share of the benefits of tech-enabled abundance

- Highlighting credible paths forward to much better lifestyles in the future, as opposed to people seeing only a bleak future ahead of them

- High-quality (but potentially low-cost) mental therapy, perhaps delivered in part by emotionally intelligent AI systems

- Addressing the person’s physical and social wellbeing, which are often closely linked to their emotional wellbeing.

In any case, worries about “resources being wasted” will gradually diminish, as technology progresses further, removing more and more aspects of scarcity. (Concerns about waste arise primarily when resources are scarce.)

It is that same technological progress that answers the second objection, namely that a UGI will be needed rather than a UBI. The point is that the cost of a UGI soon won’t be much more than the cost of a UBI. That’s provided that the economy has indeed been managed in line with the guiding principle offered earlier, namely the prioritisation of the reduction of prices for all goods and services that are fundamental to human flourishing.

In the meantime, turning to the third objection, payments in support of UGI can come from a selection of the following sources:

- Stronger measures to counter tax evasion, addressing issues exposed by the Panama Papers as well as unnecessary inconsistencies of different national tax systems

- Increased licence fees and other “rents” paid by organisations who specially benefit from public assets such as land, the legal system, the educational system, the wireless spectrum, and so on

- Increased taxes on activities with negative externalities, such as a carbon tax for activities leading to greenhouse gas emissions, and a Tobin tax on excess short-term financial transactions

- A higher marginal tax on extreme income and/or wealth

- Reductions in budgets such as healthcare, prisons, and defence, where the needs should reduce once people’s mental wellbeing has increased

- Reductions in the budget for the administration of currently overcomplex means-tested benefits.

Some of these increased taxes might encourage business leaders to relocate their businesses abroad. However, it’s in the long-term interest of each different country to coordinate regarding the levels of corporation tax, thereby deterring such relocations.

That brings us to the final objection: that a UGI needs, somehow, to be a GUGI – a global universal generous income – which makes it (so it is claimed) particularly challenging.

B8: The international dimension

Just as the relationship between two or more people is characterised by a combination of collaboration and competition, so it is with the relationship between two or more countries.

Sometimes both countries benefit from an exchange of trade. For example, country A might provide low-cost, high-calibre remote workers – software developers, financial analysts, and help-desk staff. In return, country B provides hard currency, enabling people in country A to purchase items of consumer electronics designed in country B.

Sometimes the relationship is more complicated. For example, country C might gain a competitive advantage over country D in the creation of textiles, or in the production of oil, obliging country D to find new ways to distinguish itself on the world market. And in these cases, sometimes country D could find itself being left behind, as a country.

Just as the fast improvements in artificial intelligence and other technologies are complicating the operation of national economies, they are also complicating the operation of the international economy:

- Countries which used to earn valuable income from overseas due to their remote workers in fields such as software development, financial analysis, and help desks, will find that the same tasks can now be performed better by AI systems, removing the demand for offshore personnel and temporary worker visas

- Countries whose products and services were previously “nearly good enough” will find that they increasingly lose out to products and services provided by other countries, on account of faster transmission of both electronic and physical goods

- The tendencies within countries for the successful companies to be increasingly wealthy, leaving others behind, will be mirrored at the international level: successful countries will become increasingly powerful, leaving others behind.

Just as the local versions of these tensions pose problems inside countries, the international versions of these tensions pose problems at the geopolitical level. In both cases, the extreme possibility is that a minority of angry, alienated people might unleash a horrific campaign of terror. A less extreme possibility – which is still one to be avoided – is to exist in a world full of bitter resentment, hostile intentions, hundreds of millions of people seeking to migrate to more prosperous countries, and borders which are patrolled to avoid uninvited immigration.

Just as there is a variety of possible responses to the scenario of the Economic Singularity within one country, there is a similar variety of possible responses to the international version of the problem:

- Disbelieve that there is any fundamental new challenge arising. Tell people in countries around the world that their destiny is within their own hands; all they need to do is buckle down, reskill, and find new ways of bringing adequate income to their countries

- Accept that there will be many countries losing out, and take comprehensive steps to ensure that migration is carefully controlled

- Resist the growth in the use of intelligent automation technologies in industries that are particularly important to various third world countries

- Urge people in third world countries to plan to simplify their lifestyles, preparing to exist at a lower degree of flourishing than, say, in the US and the EU, but finding alternative pathways to personal satisfaction

- Enhance the mechanisms used globally for the redistribution of the fruits of technology.

You won’t be surprised to hear that I recommend, again, the “enhance” option from this list.

What underpins that conclusion is my prediction that the fruits of forthcoming technological improvements won’t just be sufficient for a good quality of life in a few countries. They’ll enable a good quality of life for everyone all around the world.

I’m thinking of the revolutions that are gathering pace in four overlapping fields of technology: nanotech, biotech, infotech, and cognotech, or NBIC for short. In combination, these NBIC revolutions offer enormous new possibilities:

- Nanotech will transform the fields of energy and manufacturing

- Biotech will transform the fields of agriculture and healthcare

- Cognotech will transform the fields of education and entertainment

- Infotech will, by enabling greater application of intelligence, accelerate all the above improvements (and more).

But, once again, these developments will take time. Just as national economies cannot, overnight, move to a new phase in which abundance completely replaces scarcity, so also will the transformation of the international economy require a number of stages. It is the turbulent transitional stages that will prove the most dangerous.

Once again, my recommendation for the best way forwards is the mixed model – local autonomy, aided and supported by an evolving international framework. It’s not a question of top-down control versus bottom-up emergence. It’s a question of utilising both these forces.

Once again, wise use of new technology can enhance how this mixed model operates.

Once again, it will be new metrics that guide us in our progress forward. The UN’s framework of SDGs – sustainable development goals – is a useful starting point, but it sets the bar too low. Rather than (in effect) considering “sustainability with less”, it needs to more vigorously embrace “sustainability with more” – or as I have called it, “Sustainable superabundance for all”.

B9: Anticipating a new mindset

The vision of the near future that I’ve painted may strike some readers as hopelessly impractical. Critics may say:

- “Countries will never cooperate sufficiently, especially when they have very different political outlooks”

- “Even within individual countries, the wealthy will resist parts of their wealth being redistributed to the rest of the population”

- “Look, the world is getting worse – by many metrics – rather than getting better”.

But here’s why I predict that positive changes can accelerate.

First, alongside the metrics of deterioration in some aspects of life, there are plenty of metrics of improvement. Things are getting better at the same time as other things are getting worse. The key question is whether the things getting better can assist with a sufficiently quick reversal of the things that are getting worse.

Second, history has plenty of examples of cooperation between groups of people that previously felt alien or hostile toward each other. What catalyses collaboration is the shared perception of enormous transcendent challenges and opportunities. It’s becoming increasingly clear to governments of all stripes around that world that, if tomorrow’s technology goes wrong, it could prove catastrophic in so many ways. That shared realisation has the potential to inspire political and other leaders to find new methods for collaboration and reconciliation.

As an example, consider various unprecedented measures that followed the tragedies of the Second World War:

- Marshall Plan investments in Europe and Japan

- The Bretton Woods framework for economic stability

- The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank

- The United Nations.

Third, it’s true that political and other leaders frequently become distracted. They may resolve, for a brief period of time, to seek new international methods for dealing with challenges like the Economic Singularity, but then rush off to whatever new political scandal takes their attention. Accordingly, we should not expect politicians to solve these problems by themselves. But what we can expect them to do is to ask their advisors for suggestions, and these advisors will in turn look to futurist groups around the world for assistance.

C: The vital questions arising

Having laid out my analysis, it’s time to ask for feedback. After all, collaborative intelligence can achieve much more than individual intelligence.

So, what are your views? Do you have anything to add or change regarding the various accounts given above:

- Assessments of growing societal inequality

- Assessments of the role of new technologies in increasing (or decreasing) inequality

- The likely ability of automation technologies, before long, to handle non-routine tasks, including compassion, creativity, and common sense

- The plausibility of the “Turing Trap” analysis

- Repeated delays in the replacement of GDP with more suitable all-round measures of human flourishing

- The ways in which new forms of AI could supercharge centralised planning

- The reasons why some recipients of welfare squander the payments they receive

- The uses of new technology to address poor emotional health